Frida Kahlo: a matter of love, commitment, and identity

July is synonymous with Frida Kahlo, as she was both born and died in this month. That’s why we want to return to the artist, to the person, this time through the lens of art historian and exhibition curator Dr. Helga Prignitz-Poda, who has studied Kahlo’s work in depth from a biographical perspective, both as an artist and as a woman. As an expert and co-author of the Study Book included in the edition The dreams of Frida Kahlo, Prignitz not only delves into the finest details of the drawings that inspired the book, but also, through informal conversations and interviews, offers a more personal view of Frida—key to understanding her artistic creation.

Love through style and color

“Yes, her early paintings were influenced by Diego, but after her thirties […], after they had traveled to the United States, she freed herself from Diego’s artistic influence and new ones began to enter her painting, like Surrealism, which she encountered in the United States. Until her death, Diego always supported her painting.”

Romantic love not only shaped Frida’s personal life, but also served as an artistic influence evident in both the message and the technique of her paintings. She met her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera, first as her teacher. Frida adored him, and that fine line between admiration and love was one they both ultimately crossed. Art brought them together, although once the romantic relationship was established and their classroom days were behind them, Frida found her own creative style, one no longer so heavily influenced by Rivera.

“Sepia is the ink an octopus uses to hide itself. And in the same way, Frida uses sepia to hide. These are very secret drawings. […] Between 1946 and 1952, she illustrated the love and the secret relationship she had with Josep Bartolí.”

PRINT 30, Sepia drawing Sadja 379, 1946. Pencil on paper, 27.3 cm x 20.3 cm. University of Texas, Blanton Museum of Art Collection. Gift of Judy S. and Charles W. Tate, 2016.

© Banco de México, Trustee in the Trust for the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

One of the most fascinating aspects of her painting was her distinctive use of sepia tones, which at the time was seen as a purely aesthetic choice. However, as Prignitz points out, it goes beyond color: it functions as a translucent veil meant to conceal, to bury her most inappropriate or reproachable thoughts and feelings, like the betrayal of falling in love with Josep Bartolí, a man who was not her husband.

Social and political commitment in her art and life

Frida Kahlo’s work was always engaged with the society and politics of her time, always from a forward-looking perspective. This spirit lives especially in her self-portraits, embodying communist and feminist voices within her face and figure.

“The self-portrait is more political, and [André] Breton discovered this when he described Frida’s work as a ribbon wrapped around a bomb. […] She always wanted her work to be more useful to the communist movement […], but the work is political because she turned her personal life into politics, she freed herself from many societal norms, and that too is political.”

Left: PRINT 5, Atomic Bomb, c. 1951. Pencil on paper, 29.5 x 22.2 cm. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th-Century Mexican Art and Vergel Foundation. ©Photo: Gerardo Suter.

Right: PRINT 13, Frida and the abortion, 1932. Lithograph, 32.5 x 24.5 cm (with frame). Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico. ©2021. Photo Schalkwijk/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

© Banco de México, Trustee in the Trust for the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

These messages are rarely the central theme of her pieces, but rather a subtext, a predetermined foundation on which all subjects are build: the essence of her work. Like a soundtrack playing in the background, political and social themes didn’t need to be the main focus of her paintings or drawings. Frida expressed them simultaneously and directly by supporting refugees from Spain and Germany, for example, or simply by portraying herself outside the idea of womanhood of her time.

“She gave so much to the women of the world, to free themselves, to break away from what’s regular and normal, to give them the strength to trust themselves. Frida is a symbol of that, and through her art, she contributed significantly to the feminist movement.”

An identity that splits through art

“In all her work, you can feel the division of Frida into two personalities. She describes in her memoirs that the origin of this split began in childhood and that she found help in an imaginary friend. […] There is one Frida, the white, innocent one from childhood, from a past time; and the other Frida is a mask she put on, like a costume, to portray the Frida she wanted to be but never was.”

She painted for many reasons: painting was both a manifestation or residue of love, a commitment to her time, and above all, a private act that she did for her own. With every brushstroke, she came closer to herself, and in doing so, created enough distance to conceive two opposite but complementary states of being: her fulfilled self and her frustrated or unattainable self. Between these two personas—the one who suffered and the one she wanted to be—lies the most authentic Frida.

“You would have to read all her books to understand all her paintings.”

The Two Fridas, 1939. Oil on canvas, 172 x 172 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

© Banco de México, Trustee in the Trust for the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

In a way, having discovered this duality through creation suggests that her person was inseparable from her artistic self. Likewise, her work cannot be fully understood without knowing those sides of her kept away from the gallery —her most intimate, personal face. It is a bond so inseparable that it raises an interesting debate: was Frida the one who made art, or was it art that made Frida?

“It’s impossible to separate life from painting. […] Even if you try to describe the painting only through its iconography or style, you always have to go back to the moment she painted it. […] She painted her inner biography, her spiritual biography, not so much the events.”

The dreams of Frida Kahlo: the person behind the artist

– A numbered and limited edition of 2,998 copies, already sold out.

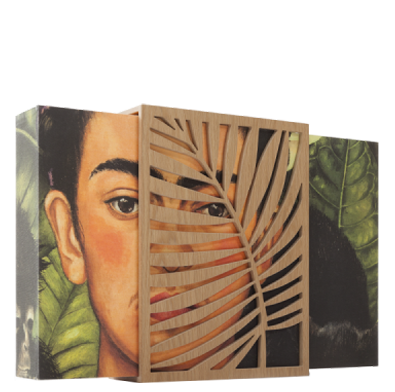

– This edition includes two volumes and a spectacular display case that presents the artist’s gaze, one that watches and captivates from behind a veil of carved wooden leaves.

– The Art Book features 34 full-scale plates of the artist’s work, reproduced with outstanding fidelity.

– In the Study Book, the greatest experts on Frida lend their voices: María del Sol Argüelles, director of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo House Studio Museum; journalist, poet, and Diego’s grandson, Juan Rafael Coronel Rivera; and art historian and curator Helga Prignitz-Poda.

– Rounding out the edition is an artist’s portfolio with a reproduction of El pájaro nalgón (The Big Bird), a large-format drawing.