Celebrating the Month of Frida Kahlo by sharing her perspective of the world

In the month of her birth and death, we remember the legendary Mexican painter Frida Kahlo: one of the most influential artists in recent history and an icon of popular culture. A nonconformist woman ahead of her time, Frida broke stereotypes and continues to inspire new generations. Although her self-portraits are her most famous works, the portraits of family, friends, and romances are another key piece that reveals how Frida viewed and interpreted her surroundings and the people around her.

Frida Kahlo was a great portraitist, albeit not a conventional one. Like her self-portraits, through which she could uniquely capture her physical and emotional pain, her portraits were always laden with symbolism and visual metaphors, supported by an aesthetic identifiable with nature and Mexican popular culture.

One fascinating aspect of her portraits is the wide variety of styles. While some of her drawings demonstrated her ability to capture reality faithfully, in others, she wanted to escape from that realism typical of the format to explore unique ways of representing people. Symbolism, humor, and irony were key tools for those drawings, capable of encapsulating the essence she perceived in people and relationships.

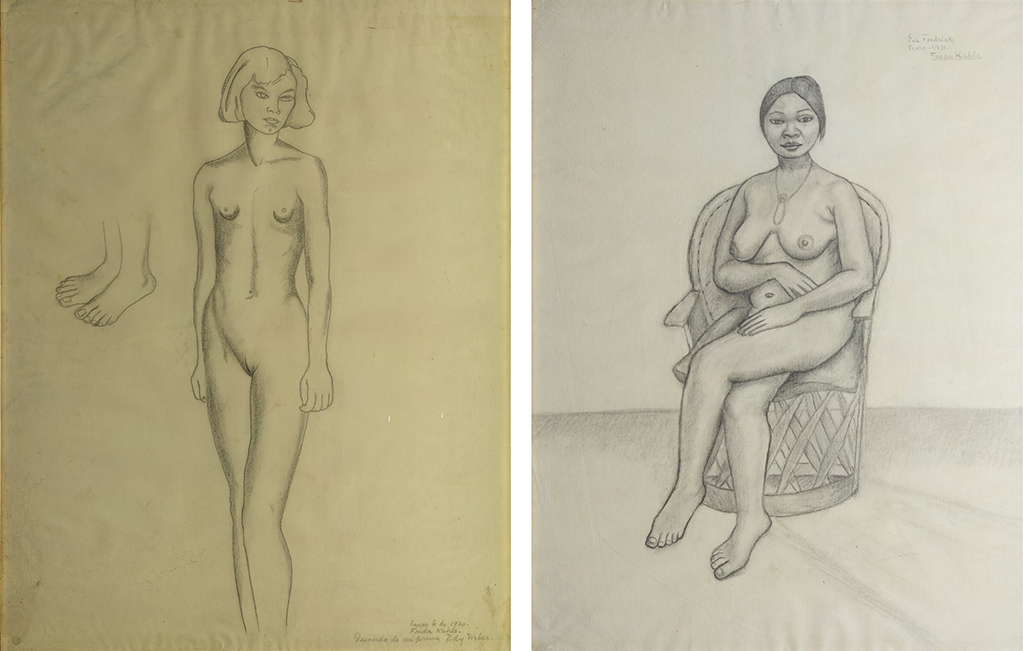

A notable drawing from the early ’30s is Nude of My Cousin Ady Weber. Here, Frida’s play is hidden not in the drawing, which is more realistic, but in the name. It is not recorded that Frida had a cousin named Ady. However, the Weber family of jewelers moved near the Kahlos with a daughter named Ady who was very interested in art. “Cousin”, “Prima” in its original Spanish version, may refer not to kinship but to “first,” suggesting that it was Frida’s first nude portrait.

It wouldn’t be the last. Shortly after, Frida painted Nude of Eva Frederick, a New York model for Diego Rivera, Frida’s husband. The artist took the opportunity to have a professional model and continued to explore her skill as a portraitist, making a more harmonious and balanced nude than the previous one, as well as a portrait of her face.

Left: Nude of Ady Weber, My Cousin, 1930. Right: Nude of Eva Frederick, 1931. © Banco de México, Trustee in the Trust for the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

Another person in her husband’s circle whom she used to refine her technique was Cristina Hastings, wife of John Hastings, Diego’s assistant. The detail and realism shown in her paintings of this period would be left behind in favor of comedic symbolism full of irony and personal codes that could make it difficult to recognize the person portrayed.

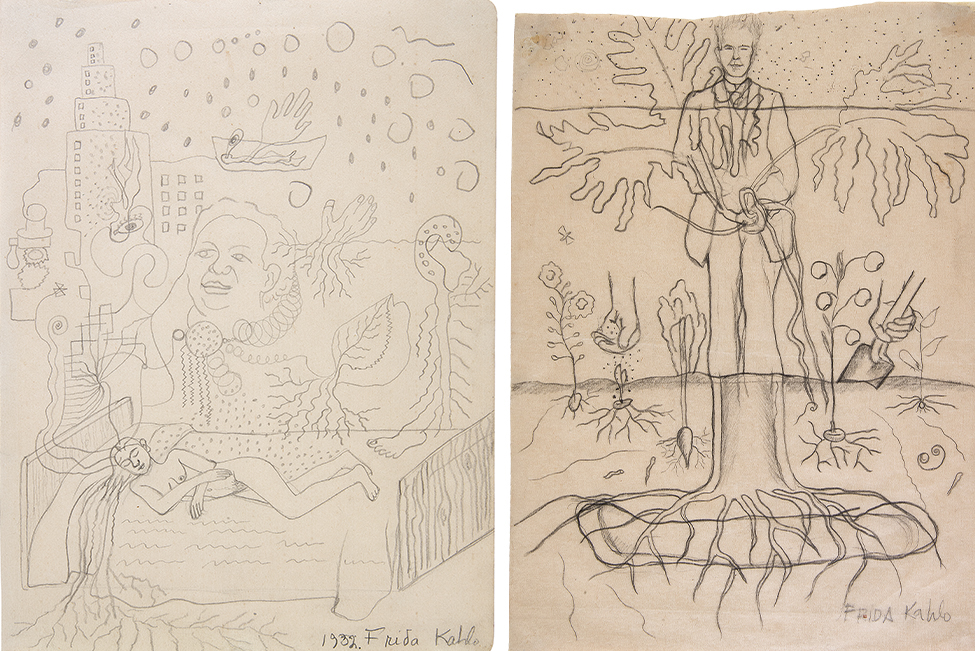

At this point, Frida invented a completely original way of portraying her loved ones: she placed the subject in a hair salon experiencing a real makeover that made them practically unrecognizable. This playful and carefree technique concealed numerous details and nods to reality that have led to many analyses.

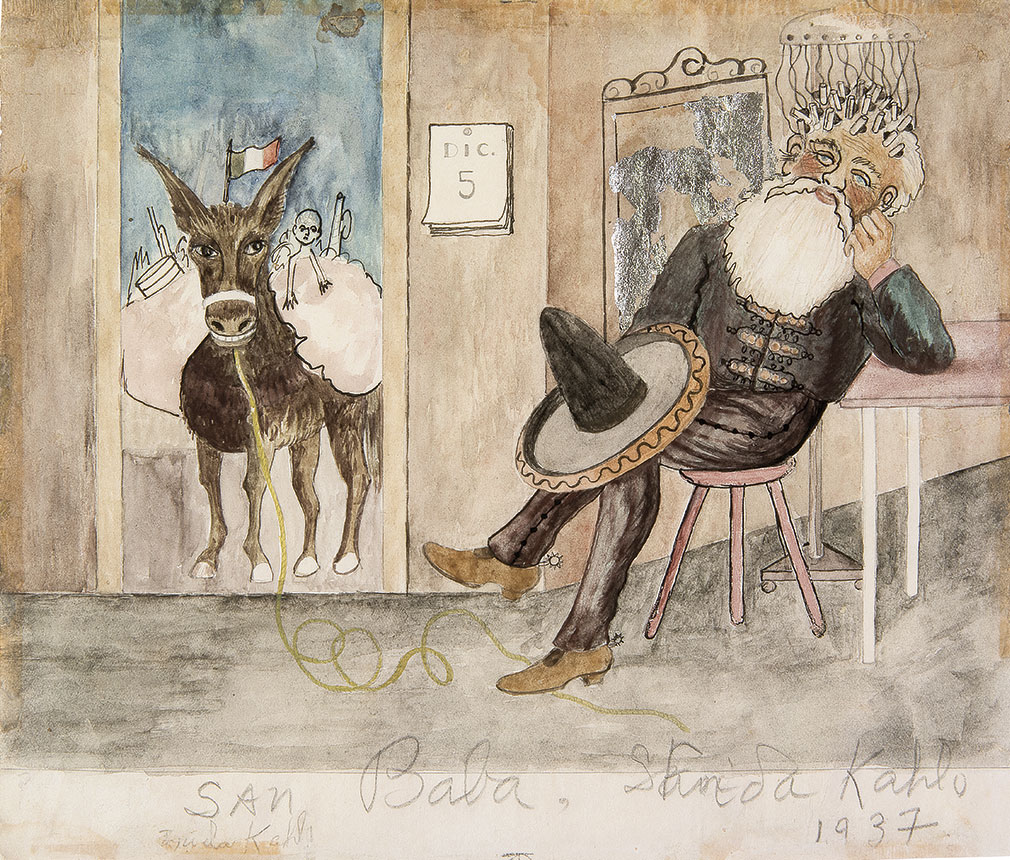

Watercolors like The Permanent, San Baba or Beauty Salon are clear exponents of this resource, and even in their titles, as in their drawings, something is hidden. Thus, the title of the former does not refer to the permanent hairstyle technique but reveals the identity of the caricatured hairstyle: Nickolas Murray, Frida’s lover for more than a decade, whom she depicted with echoes of Santa Claus, who “brings joy and happiness”.

In San Baba, the “victim” is none other than the revolutionary Trotsky, adorned with symbols of the politician’s interest in his hostess in Mexico and his excessive flattery, earning him the nickname of the flattering saint. Finally, in Beauty Salon, her friend Lola Álvarez is subtly represented, with Frida alluding to her by including numbers assigned to the initials of her name. The hair salon serves as a meeting and beautification setting.

San Baba, 1937. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico. © Photo: Rafael Doniz. © 2021 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2 col. Centro alc. Cuauhtémoc c.p. 06000 Mexico City.

Another person from her circle whom she portrayed originally was Antonio Rodríguez, art critic of the Mexican magazine Así, who interviewed Frida. She captured this situation in a sort of symbolic dialogue interweaving elements both her own and those of the journalist, thus portraying not faithfully both interlocutors but the situation itself, the conversation, and the coquettish tension captured in the title: With Love for Toño.

Moving further away from realism, Frida began to connect points in her works with lines crossing her drawings in an exercise of existential reflection: proof of the union of ideas and internal dialogue. While the Venezuelan writer Juan Rohl was one of the greats portrayed under this experimental lens, notable are the “portraits” Vacilando and Sun and Moon of her idealized father in the latter drawing with two well-encased stars, showing their good relationship.

The last portraits were dedicated to the psychologist Olga Campos, with renewed elegance, posing her beautiful face on a firm neck and large eyes and ears, a metaphor for the stability she provided by listening to her. Thus, the painter closes the circle, leaving behind the comedic and surreal strokes and returning to a faithful style, a sign of respect and affection for this woman, as she did with her early female subjects in contrast to certain male figures.

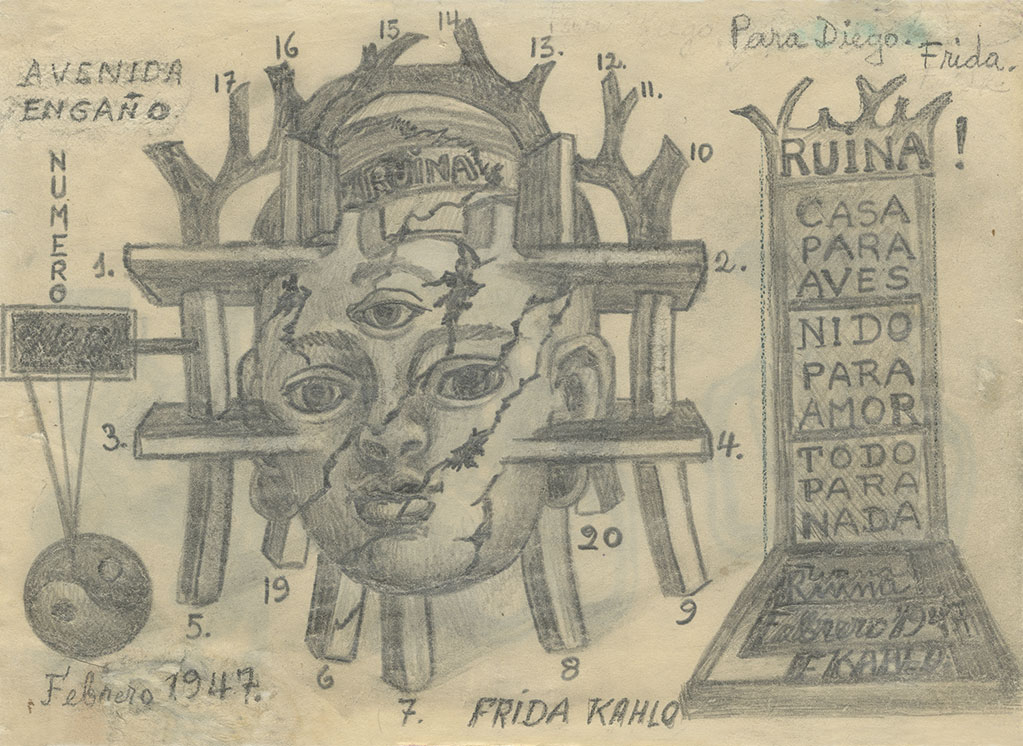

But, of course, her husband, the artist Diego Rivera, played a fundamental role in Frida’s portraits, the love of her life, and her greatest torment. This is how she portrayed him: sometimes with beautiful realism; other times satirical, exaggerated, and caricatured; and even in surreal forms, represented as a dependent baby, a shadow in Frida’s mind over her characteristic eyebrows, or as a calamity under the illustrative title of Ruin.

Ruin, 1947. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico. © Photo: Rafael Doniz. © 2021 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2 col. Centro alc. Cuauhtémoc c.p. 06000 Mexico City.

Although these drawings were not conceived for public display, history has placed them in their deserved place, admired by millions of people. With enormous research work, ARTIKA gathers in The Dreams of Frida Kahlo the most memorable works of this iconic artist, immersing the reader in a world of overflowing imagination.

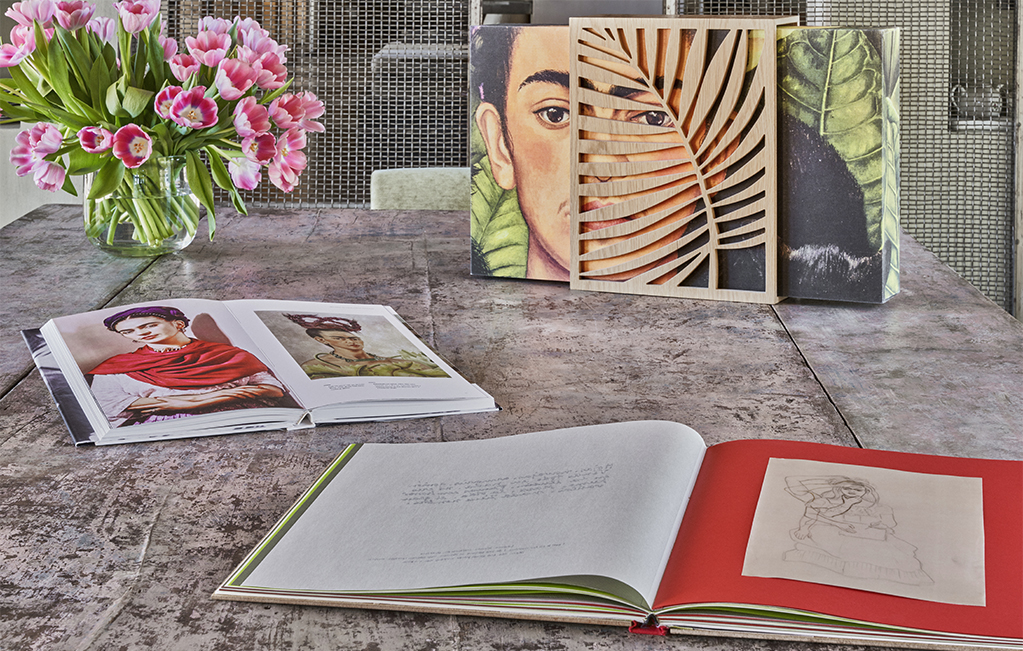

The Dreams of Frida Kahlo: a journey to the mind and heart of the iconic artist

ARTIKA and the foremost experts on the figure and legacy of the Mexican painter join forces to revive the art, passion, and message of Frida Kahlo, gathering her most important drawings and reflecting on the values and symbolism hidden behind them.

– Limited and numbered edition of 2,998 copies, already sold out.

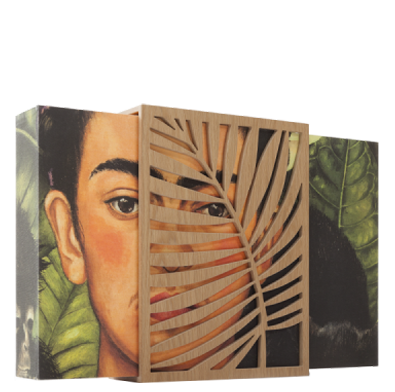

– The work includes two volumes and a spectacular display case that shows Frida’s penetrating gaze behind a veil of wood-carved leaves.

– The Art Book presents 34 original-scale sheets with works by the artist reproduced with excellent fidelity.

– In the Study Book, the voices of the foremost experts on Frida contribute: María del Sol Argüelles San Millán, director of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo House Museum; journalist, poet, and Diego’s grandson Juan Rafael Coronel Rivera; and art historian and exhibition curator Helga Prignitz-Poda.

– It also includes an artist’s portfolio with the reproduction of a spectacular large-sized sheet featuring the work El pájaro nalgón (The Big Bird).