Valdés in action: the basis of his artistic creation

Manolo Valdés describes himself as “very protective of my time, my habits, and my things”, traits that are, in fact, the birthplace of his art. While creating is essential for his life, it is life itself that ultimately yields to the demands of artistic production, taking him across the globe, decontextualizing the past, and giving color to what was once invisible.

New York: the starting point

“I always say I discovered freedom when I realized things could be different. The indigestion I brought back from Paris, I tried to take her to the School of Fine Arts, which turned out to be a disaster. […] I ended up getting expelled.”

Valdés, who came from Valencia –a place where art had to stay within the line, never splatter beyond the canvas or break the mold—, began traveling while still studying at the School of Fine Arts. Suddenly, going home wasn’t so much a step back as a step against his own growth and artistic potential. The concept of home was redefined, and the artist within him would fade when creation became dictated by the environment rather than inspired by it. What began as a three-month stay in New York became thirty years—and counting—in that iconic city.

“New York is a city that leans toward excellence, a city full of information. […] Those of us who can access information have advantages.”

Manolo Valdés in his New York studio.

Madrid —where the Prado Museum is located— would have been enough if he had wanted to be just a painter. But in New York, he discovered a creative freedom that didn’t limit artistic expression to painting alone. Travel had opened his eyes, and New York was the shared studio of the world’s artist, rich, diverse, and surprising —a city that, since then, has been nourishing him and encouraging him to write his own rules.

Influences: the pretext for innovation

“The influences from any artwork you’re interested in at the time are brought into your own world so you can comment on what they’re doing.”

Velázquez, Miró, and Picasso, among others, reaffirm Valdés’s deep enthusiasm for art. During his first visit to the Prado, he encountered Velázquez through Las Meninas, before the renovations and relocations, when the room still enjoyed natural lighting. Since then, he has continually revisited the painting —both in the museum and in his own work— bringing it to life temporarily on the streets of New York, Bilbao, or Venice, or permanently through pieces like our edition Damas y Caballeros: Manolo Valdés. Picasso’s and Miró’s prints also captivated him, their techniques transformed into textures that adapt to movements like Pop Art to reinterpret those figures and turn them into something entirely new.

Left: detail of the painting of Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez, 1957.

Right: Las Meninas, sculpture group by Manolo Valdés in Hofgarten gardens, Düsseldorf, 2006.

Obsession: his eternal companion

“I never choose something that doesn’t obsess me, that doesn’t interest me. […] The chosen painting is always a mystery. […] Suddenly, you don’t know how something enters your mind —to never leave it, either.”

Just like with Queen Mariana or Infanta Margarita, once something enters Valdés’s mind, it rarely escapes. His personal and artistic identities are one and the same; neither exists without the other, and they are linked by the artist’s constant obsession with life’s latent but unexpected moments. There are things —smells, objects, people, words— that populate reality and pass through our everyday lives unnoticed. Then, suddenly and accidentally, we become aware of them and, after that, we can no longer ignore them. They become part of us, and we ourselves of them. That’s what happens to the artist, and sometimes his art becomes a reaction to what’s been overlooked.

Left: detail of the portrait of La Infanta Margarita en azul by Velázquez, 1659.

Middle: Infanta Margarita azul, Paris, 2020.

Right: Infanta Margarita, London, 2021.

“What I never do is stop working on a painting just because I’ve created upon it before. The feeling that stays after I’ve finish is, actually, that I’ve said too little. Painting isn’t like film; there are no sequences, you can’t tell the whole story. […] I have no fear of something staying with me year after year.”

He can’t discard the idea—if anything, it must abandon him. Ideas should fall away naturally, not be forced out; they should rest only when they are tired and die only when their time has come. That obsession —loyalty based to what moves him, rather than shame or restraint— is what gives his work a sense of healthy nostalgia, keeping the art of the past alive without looking back.

The female figure: his favorite subgenre

Around 80% of Valdés’s work centers on the female figure, something the artist says isn’t intentional, though he acknowledges it aligns with art history’s narrative: the woman as vanishing point, motif, structure, the bridge between inspiration and creation, and also the final destination.

“When I see sculptures commemorating something specific, like generals or writers, they don’t interest me as much as the abstract figure. That’s a genre, to me. And within that, the female figure.”

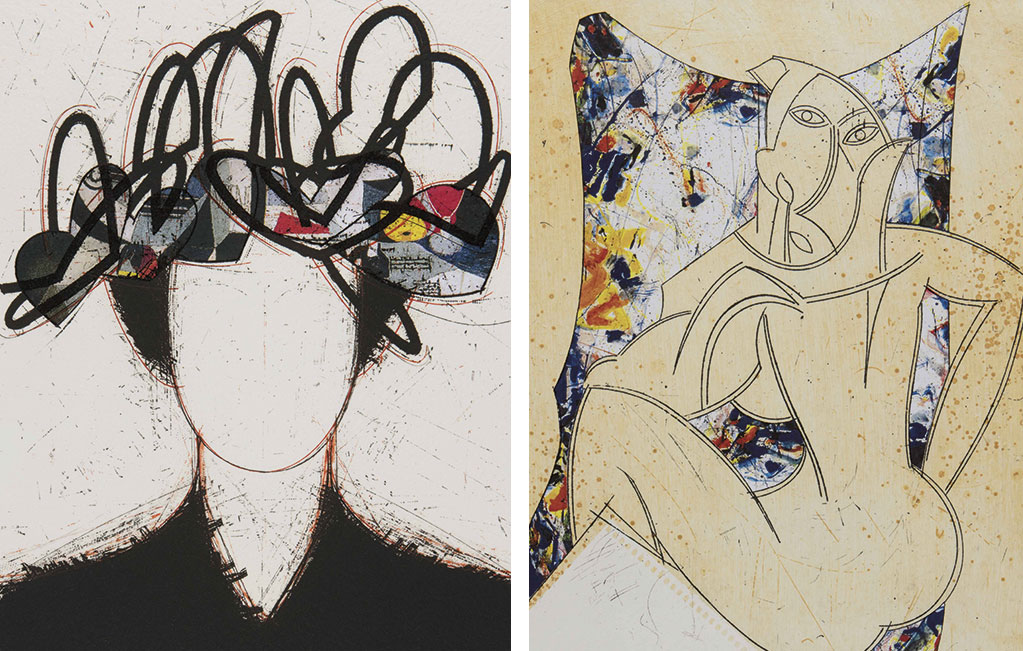

Left: detail of Helène VIII, 2005. Co-edition ARTIKA-Manolo Valdés. © Manolo Valdés Studio, 2023

Right: detail of Pamela IV, 2013. Co-edition ARTIKA-Manolo Valdés. © Manolo Valdés Studio, 2023

For Valdés, whatever quality the female form possesses that other shapes —living or not— do not, is both unknown and irrelevant. When inspiration strikes, he doesn’t question it; doing so would be like trying to breathe air robbed of oxygen. Thus, the female figure is not simply a recurring theme in his work, but rather a subgenre that shares equal footing with the techniques and materials of his practice: essential, primary, and unmistakably his.

Left: Edna, 2008. Co-edition ARTIKA-Manolo Valdés. © Manolo Valdés Studio, 2023

Right: El cubismo como pretexto 8, 2003. Co-edition ARTIKA-Manolo Valdés. © Manolo Valdés Studio, 2023

Damas y Caballeros: Manolo Valdés, a conversation with the past in the present

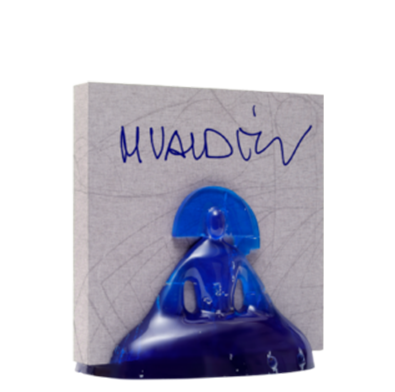

– A numbered and limited edition of 998 copies, each individually signed by the artist

– The edition includes two volumes and a sculptural case that is itself a work of art. Featuring a reinterpretation of Velázquez’s menina crafted by hand, each piece is unique due to its cracks and imperfections.

– The Art Book features 53 paintings, prints, and collages from Valdés’s most representative periods, personally selected by the artist and reproduced with the highest quality.

– The Study Book brings together insights from leading experts in four chapters that explore Valdés’s career, his body of work, and his influences.