The romanticism of Sorolla: Clotilde, the soul of his inspiration

Joaquín Sorolla was not only a virtuoso painter—he was also, on many occasions, an exceptional draftsman (over 5,000 drawings are preserved) and a gifted writer. For years, Sorolla exchanged letters with his wife, Clotilde García del Castillo, through which he expressed his deep devotion and feelings for her. We know this side of the artist thanks to Blanca Pons-Sorolla and her uncle, Víctor Lorente Sorolla, who worked to preserve and compile these letters into a vast correspondence that collected the couple’s most intimate conversations.

Eternal love between Sorolla and Clotilde

Sorolla was able to devote himself entirely to his great passion for art thanks to his family, who surrounded him with love and supported him in all his achievements. Clotilde was essential in the artist’s life—not only as his great love but also as his guide and lifelong collaborator. Few women of her time possessed her strength and determination. Intelligent, cultured, and hardworking, she was the perfect companion for a man who lived more outside than inside his home, traveling the world to share his art.

The gesture of love and devotion Clotilde made after the artist’s death is a true testament to the profound admiration she felt for him throughout her life.

“There is no greater act of love for her husband than to bequeath everything so that it may endure. It was the last help she could offer him.” (Interview with Blanca Pons-Sorolla, exclusively for the Sorolla in Private edition)

Left: Sorolla painting the picture Señora de Sorolla in Black, 1906.

Right: Clotilde con traje negro (Señora de Sorolla in Black), 1906.

As the artist’s great-granddaughter recounted, Clotilde decided to perform an incomparable act of generosity: donating everything for the creation of the Sorolla Museum. Aware of the priceless value of her husband’s artistic legacy, she gave not only his works—paintings, drawings, and letters—but also their home, gardens, and all the objects she had so lovingly preserved. Visiting the Sorolla Museum is to step into the artist’s life, to know his essence, and to immerse oneself in the intimacy of his world. This gesture was not only meant to preserve Sorolla’s memory but also to ensure that future generations could study his art and keep alive the international recognition he achieved during his lifetime.

Thus, Clotilde turned her love into a tangible legacy, ensuring that Sorolla’s light and creative spirit would continue to inspire the world beyond his time.

The letters: a memory that endures through time

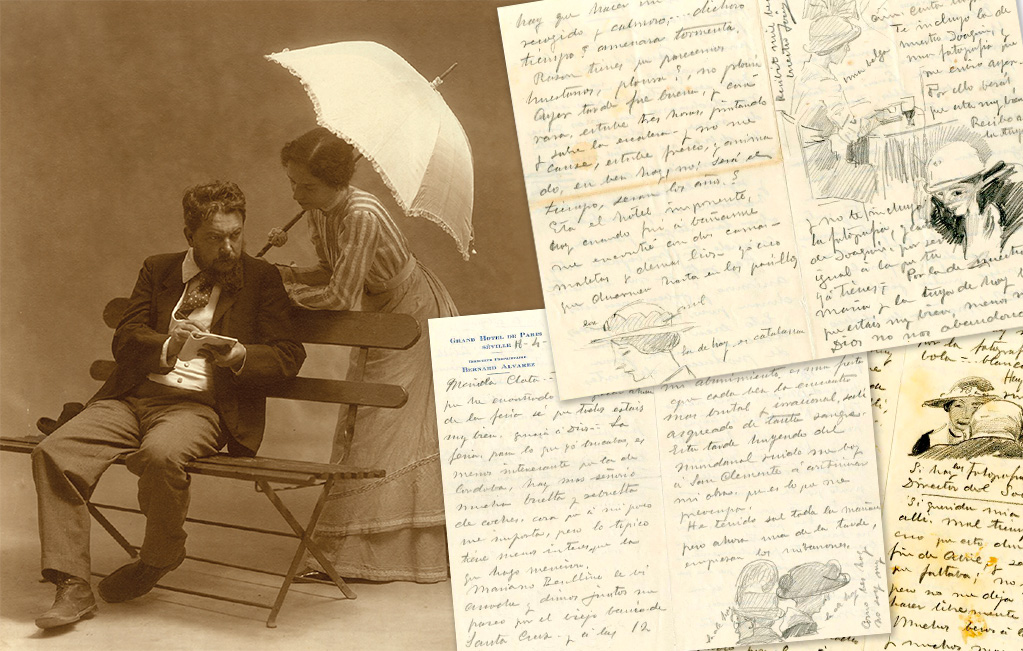

The letters were a key element in their relationship, as they were often the only way Sorolla could express his love for Clotilde when separated by great distances. In Sorolla and Clotilde: An Illustrated Love Story (a chapter written exclusively for the Sorolla in Private edition), Blanca Pons-Sorolla opens up about the most intimate side of her great-grandparents. Thanks to these letters, we can gain a deeper understanding of the extraordinary bond that united them.

Left: Joaquín Sorolla and Clotilde, 1901.

Right: Correspondence from Sorolla updating Clotilde on his stay there, while accompanying the letters with some drawings by the guests staying at the hotel., Seville, 1914.

Sorolla and Clotilde married in 1888. When their first daughter, María, was born, Clotilde stopped accompanying him as often on his travels. The distance between them grew, and so letter-writing became their lifeline to stay connected. Clotilde once wrote to her husband:

“My dear Joaquín: yesterday I didn’t write to you, and today I write so as not to lose the habit (and because it feels as though, when I write, you’re closer to me), but I don’t know where to send this yet, since I still don’t know your address in Granada.”

Their correspondence evolved into long exchanges, sometimes written in different moments of the day. In every letter, Clotilde was the center of Sorolla’s attention. To her, he confided his joys as a painter, his doubts, his moments of despair, and the emotion and tears that arose when he could express himself with peace and passion. Above all, he always expressed his profound desire to have her by his side. In 1907, Sorolla wrote:

“All my affection is concentrated in you, and although children are children, you are more—so much more… You are my flesh, my life, and my mind. You fill the void my life had as a man without a father or mother before I met you. You are my eternal ideal, and without you, nothing that now concerns us would matter at all, so there is nothing to fear.”

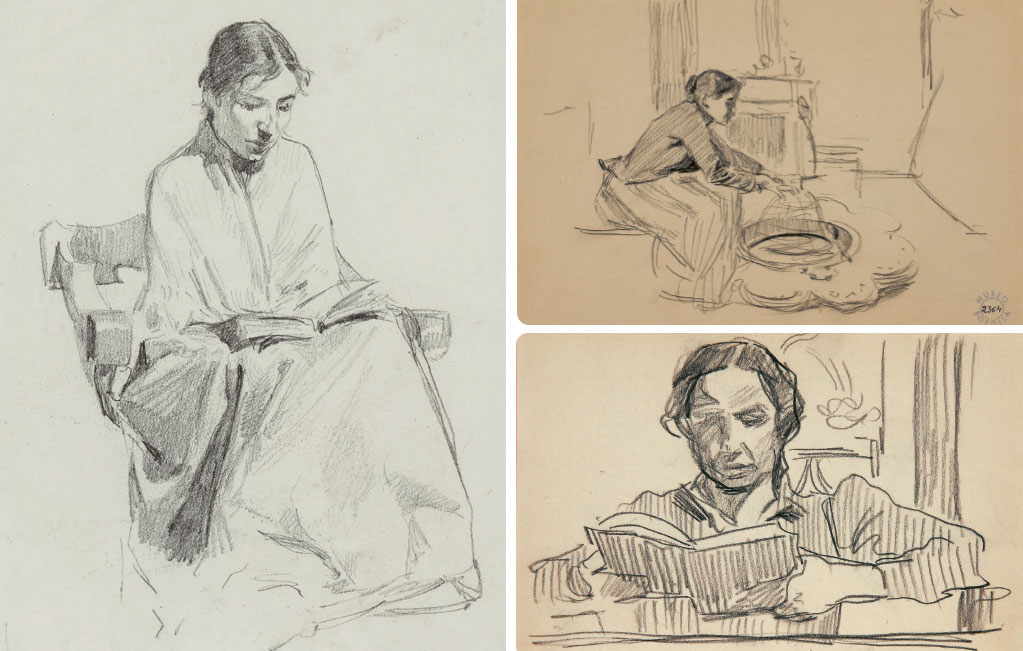

Left: Clotilde leyendo (Clotilde Reading), Asís, c. 1888.

Right Sup.: Clotilde tapando un brasero (Clotilde Covering a Brazier), c. 1891-1892.

Right Inf.: Clotilde leyendo (Clotilde Reading), Valencia, 1902.

Clotilde replied to every letter, and in many of them, she expressed her sadness over the distance that separated them, lamenting not being able to spend more time together or find a way to change that situation:

“For my part, you know I would never want to be separated from you, not even for a moment, but it also pains me that the children lose time they won’t get back. Since I can’t split myself in two, it’s my little husband who must pay the price for my having others to love and care for.”

Portraits that reveal Clotilde’s soul

Throughout his career, Sorolla painted Clotilde as a reflection of the admiration he felt for her. She was not only his muse but also his indispensable companion. The repetition was not out of habit but devotion—it was his way of honoring her. Blanca Pons-Sorolla has said that the portraits seemed more real than photographs; as she remarked, “They were truer than truth itself.” (Interview with Blanca Pons-Sorolla, exclusively for the Sorolla in Private edition)

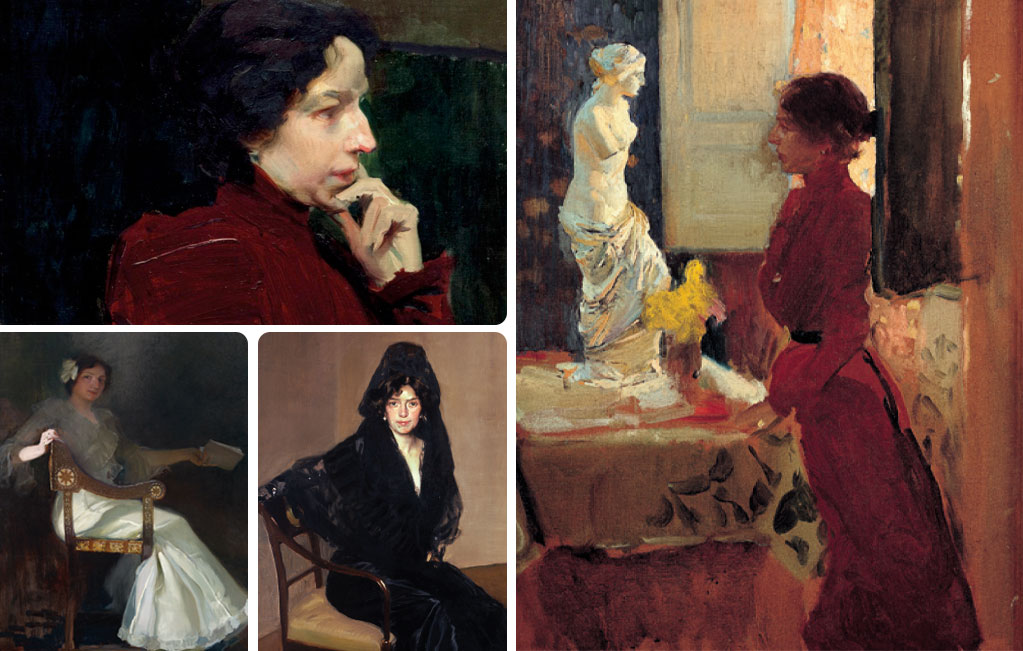

These portraits form a visual diary of how the artist saw his wife. In works such as Clotilde (c. 1902), her gaze drifts away, thoughtful and introspective, inviting the viewer to imagine her inner world.

Elegance takes center stage in portraits like Clotilde in a White Dress and Clotilde with a Spanish Mantilla (both from 1902). Her presence commands attention not only through her poise but also through the detailed rendering of her garments, emphasizing her role in high society and her refined sense of style.

Left: Clotilde, c. 1902.

Inf. left: Clotilde con traje blanco (Clotilde in a White Dress), 1902.

Inf. medium: Clotilde con mantilla española (Clotilde with a Spanish Mantilla), 1902.

Right: Clotilde contemplando la Venus de Milo (Clotilde Contemplating the

Venus de Milo), 1897.

Sorolla also portrayed Clotilde as a cultured woman, sensitive to art, as seen in Clotilde Contemplating the Venus de Milo (1897), where she is captured in a moment of aesthetic contemplation, engaged in a silent dialogue with classical beauty.

Finally, some of the most intimate portraits are those in which she appears as a mother, where tenderness and closeness take center stage. Works such as Madre (Mother, 1895–1900) reveal Clotilde’s most vulnerable and nurturing side, capturing not only her bond with her children but also Sorolla’s loving and respectful vision of motherhood.

Madre (Mother), 1895-1900.

Sorolla in Private: art as a chest of memories

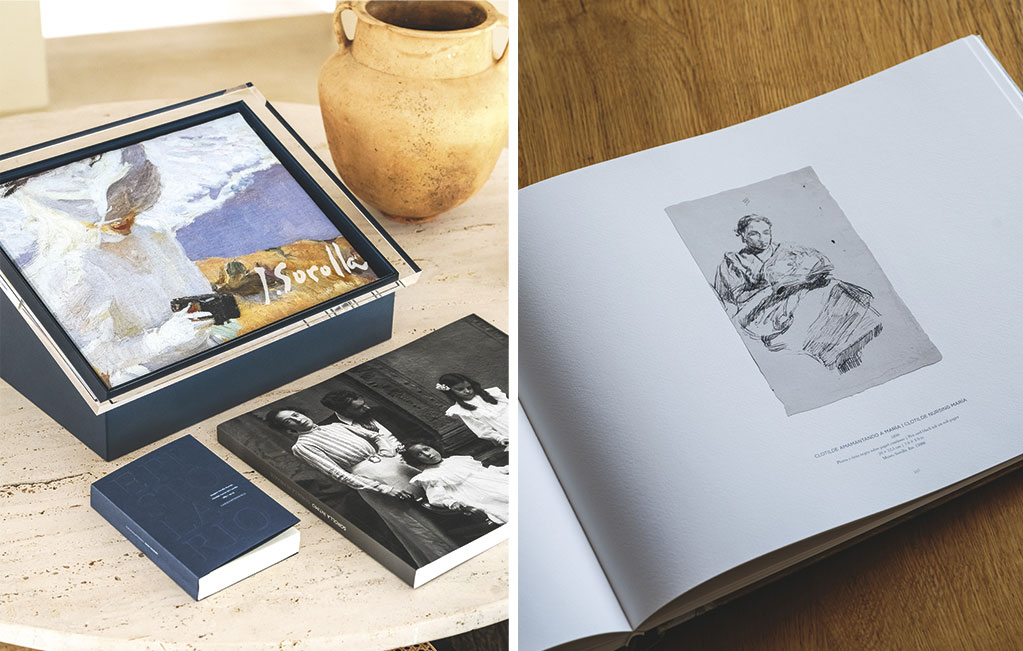

-A numbered limited edition of 2,998 copies, created in collaboration with the Sorolla Museum and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the painter’s great-granddaughter and trustee of the Foundation.

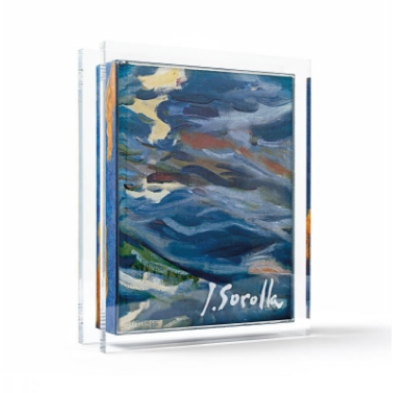

-The edition consists of two volumes, a correspondence collection, and an art print, all presented in a display case whose main image is a detail from the oil painting Instantánea, Biarritz (Snapshot, Biarritz), the cover of the Art Book.

-The Art Book includes 71 drawings that transport Sorolla’s most personal experiences into his domestic and family environment.

-In the Study Book, experts Inés Abril and Mónica Rodríguez analyze the drawings, while Blanca Pons-Sorolla, Consuelo Luca de Tena, María López, Covadonga Pitarch, and Eulalio and Pilar Pozo discuss the family and the conservation of the artist’s graphic work.

-Correspondence: three decades of love, gathers 210 of the 2,000 preserved letters. With a foreword by Isabel Justo, the letters offer not only a socio-economic and political testimony of its time but also reads as a passionate love and family story.

-The edition also includes the art print Estudio del natural (Study from Life) (c. 1905), a portrait of Clotilde rendered in charcoal, white chalk, and red oil, which once hung in the couple’s bedroom for many years.