The most private Sorolla: between art and family

Known as the master of light, he now appears under a new lens. The artist is much more than his almost photographic seascapes; Sorolla begins and ends at home with his family, making them the natural protagonists of his most personal artistic work.

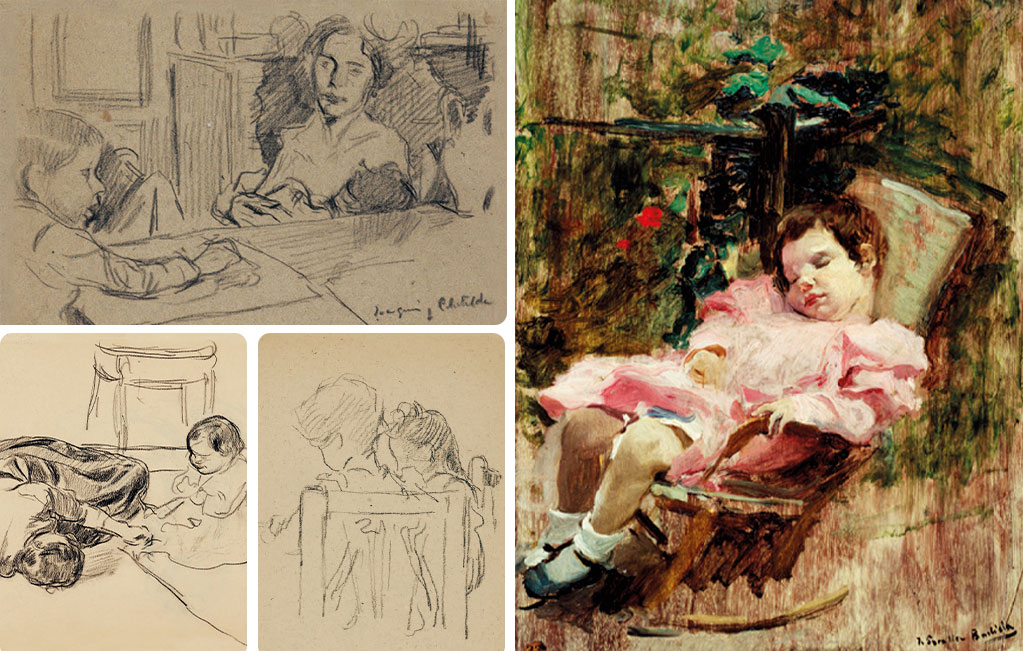

From the living room to paper: sketches that capture memories

“For him, drawing is intimate, and he seeks to reproduce all those things that slip away in seconds” – Blanca Pons-Sorolla (Patron of the Fundación Museo Sorolla and great-granddaughter of the artist).

Drawing is a reflexive act for Sorolla, an innate process that precedes everything—whether it’s a first step or an end in itself. If a painting is a building, drawing is the foundation; the pillars of a temple. However, charcoal doesn’t always reach the brush. Sorolla splits himself between his artistic and mundane selves. The act of drawing is not always a conscious endeavor; rather, it’s an irrepressible need to capture his family in fleeting moments, to understand them in all their phases and facets before time alters or replaces them.

Superior Left: Clotilde y Joaquín, c. 1898.

Inferior Left: ¡Que te come!, 1891. // Elena y María, 1900-1901.

Right: Joaquín durmiendo, 1895.

The canvas frames a moment, while paper traces an entire life. Sorolla is an incessant draftsman, as drawing is a free, immediate, and spontaneous resource that allows him to capture what painting would demand more time, more planning—more, yet somehow less, of him. His family-oriented and domestic character turns drawing into a daily activity, intertwined with the gaze through which he admires his wife and children. With every stroke, he materializes and immortalizes his love for them.

The faces of a non-portraitist: his family, his favorite models

“And that discipline he has internalized through hours and hours of drawing is what makes you think the paintings have made themselves.” – Consuelo Luca de Tena (Museum Curator and former director of the Museo Sorolla).

Sorolla is the artist of his time who most frequently portrayed his intimate life. His family members appear constantly in his paintings, contributing to the landscape as shades of blue. The painter could be traveling the world, from Rome to Paris, but upon his return to Madrid, he rarely ventured beyond his gardens, relishing his family home and the scenes that unfolded within it.

“Drawings are for him. Sorolla isn’t drawing to sell them or to gift them to his closest friends. He does it for himself, for his family,” – Blanca Pons-Sorolla.

Clotilde, Joaquín, Elena, and María are constants in his visual field. He knows them on every possible level, from their thoughts to their most instinctive gestures, so he doesn’t need them to pose to capture them on paper. The fluidity of his technique goes beyond his natural talent for drawing, and so he relies on his intrinsic understanding of the dynamics of his indoors environment and all the elements that participate in it.

Left: Madre e hijos, 1895.

Superior Right: Joaquín vestido de blanco, 1896. // Clotilde leyendo, 1896.

Inferior Right: Mi mujer y mis hijas en el jardín, 1910.

Thus, when he paints or draws his family, they are rarely formal portraits. He seeks them as part of a larger whole: walking along the beach, doing laundry, resting in the living room, reading, or sewing. Faces are often blurred to the point Clotilde and María, for instance, are indistinguishable. He also intercepts them with objects such as a camera in Instantánea, Biarritz, subjects them to challenging lighting, or simply captures them from behind.

Part of his effortlessness in portraying them comes from the absence of pressure when he’s creating only for himself. Out of the nearly 9,000 drawings he produced in his lifetime, just over half became paintings, and the gap between paper and canvas closes when he takes himself more as a father and husband rather than a world-renowned painter.

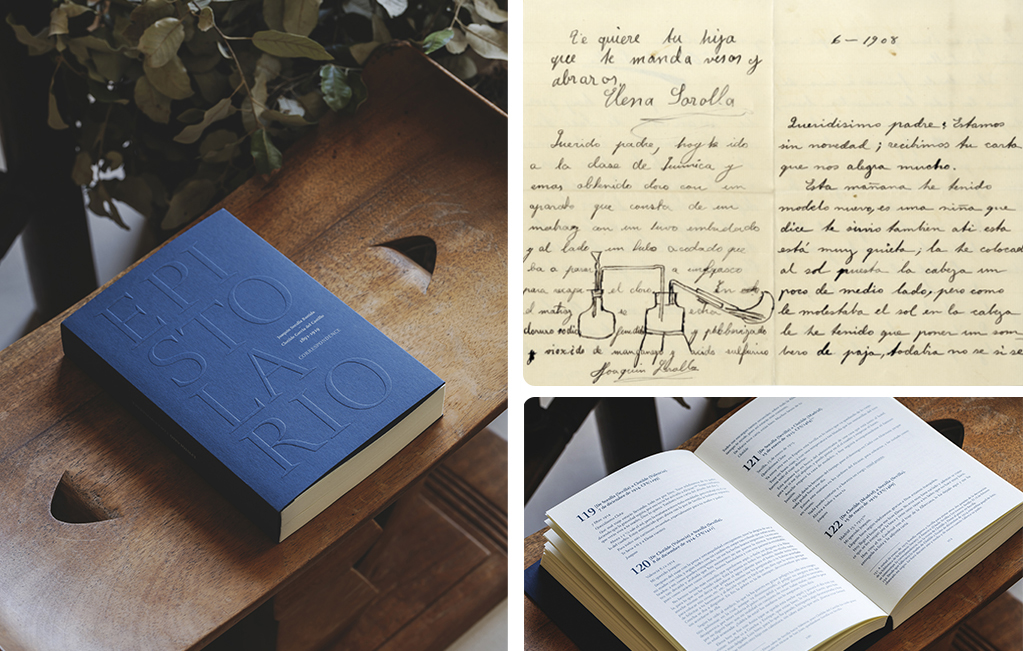

Three decades of love on paper

Sorolla In Private is more than a graphic and spontaneous landscape of his family life. For the first time, Clotilde’s letters to her husband are being published, allowing her to be seen beyond the “painter’s wife”: a multifaceted Clotilde who adds dimension to Sorolla’s figure. It’s not the sum of two halves that takes shape but the interplay of two whole individuals, with individual experiences and shared ideas, that composes the perfect picture.

“He’s speaking to anybody but her, which makes him very realistic in expressing his distress, fears, and joys.” – Blanca Pons-Sorolla.

In this back-and-forth of letters, a story full of many others emerges. The couple, separated by the painter’s travels, transcribes a social, political, economic, and artistic portrait of their time, interwoven with family anecdotes and confessions of passionate love. Ultimately, after serving as an original testimony of their contemporaneity, the correspondence becomes the piece that completes the most intimate portrait of the artist.

Painting Clotilde: Sorolla in his element

It is when Sorolla speaks of or paints his wife that he shows himself as he truly is. In a core of love, familiarity, trust, security, and freedom, the artist is able to free himself from the tensions that might hinder his stroke. Sorolla’s muse, who was also the wife and mother of his children, becomes a silhouette that is deeply recognizable in the artist’s trajectory, as well as a figure that embodies every corner of their home.

“It has that absolutely incredible movement of the moment when one rises from a chair and begins to turn around.” – Blanca Pons-Sorolla.

Estudio al natural depicts Clotilde from behind and hung for years on a wall of the master’s bedroom, increasing in value with each second it shared space with the genius. This ARTIKA artist’s book brings Sorolla closer to the world like never before, offering the contents of his notebooks and annotations, his writings, and, lastly, the full-size reproduction of this unpublished drawing.

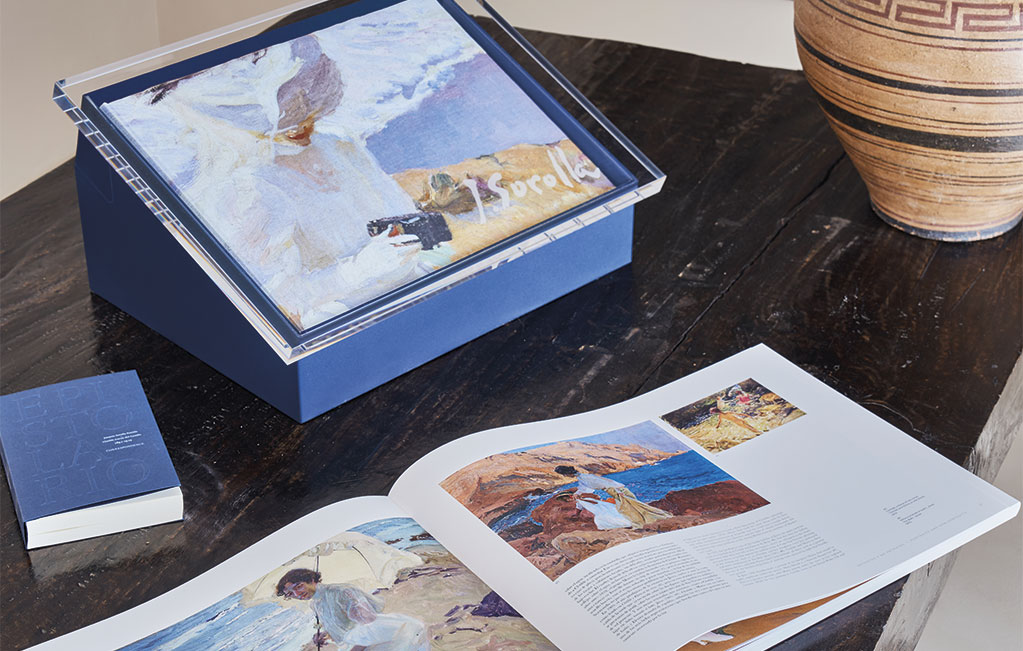

SOROLLA IN PRIVATE, a window into the artist’s inner world

– A numbered and limited edition of 2,998 copies, created in collaboration with the Museo Sorolla and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the painter’s great-granddaughter and patron of the Foundation.

– The edition consists of two volumes, an correspondence, and an art print, all encapsulated in a exhibition-case whose main image is a detail from the oil painting Instantánea, Biarrtiz, the cover of the Art Book.

– The Art Book includes 71 of his most personal drawings, previously kept in his notebooks. The selection, curated with the assistance of the Museo Sorolla and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, has been meticulously die-cut and reproduced at full scale with the highest quality.

– In the Study Book, specialists Inés Abril and Mónica Rodríguez analyze each drawing in the book, while Consuelo Luca de Tena, María López, Covadonga Pitarch, and Eulalio and Pilar Pozo address the themes of family and the conservation and restoration of the artist’s graphic work.

– The Correspondence: Three Decades of Love compiles 210 letters out of the 2,000 that are preserved. With a prologue by Isabel Justo, the correspondence serves as a socio-economic and political testimony of its time, while also reading as a story of passionate and parental love.

– The edition includes the print Estudio al natural, c.1905, a portrait of Clotilde in charcoal, chalk, and red oil that presided over the couple’s bedroom for years.