Create to regain sanity: the final year of Vincent van Gogh’s life

Van Gogh’s paintings have a timeless and hypnotic intensity, one that continues to hold us in their spell. Despite his turbulent final years, Van Gogh still managed to create some of his best works. When he was admitted to a mental hospital in 1889, he set only one condition: that he could be allowed to continue to paint. Thus, there was written a page in the history of art that could have been left blank.

A tormented spirit

After several breakdowns, at the age of 36, Vincent van Gogh was a source of concern for those close to him. Everyone thought that the artist was incapable of living on his own, particularly after the episode that followed a quarrel with Paul Gauguin in which he cut off his own ear.

In search of inner peace

On 8 May 1889, Vincent voluntarily checked himself into a small mental asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. It was the right choice, particularly since he could fulfil his desire to continue creating. In one of his letters to his brother he made this clear: “If sooner or later I get a certain amount better, it will be because I have recovered through working.”

The Irises, 1889. Oil on canvas, 71 x 93 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum

Crisis and inspiration

With a special permit, he was able to paint cypresses, olive trees, lilies and lilacs in the surroundings of the asylum. On days when he was too weak, he painted oil paintings like The Night, one of his masterpieces, from the window of his room.

Starry Night, 1889. Oil on canvas, 73 x 92 cm. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

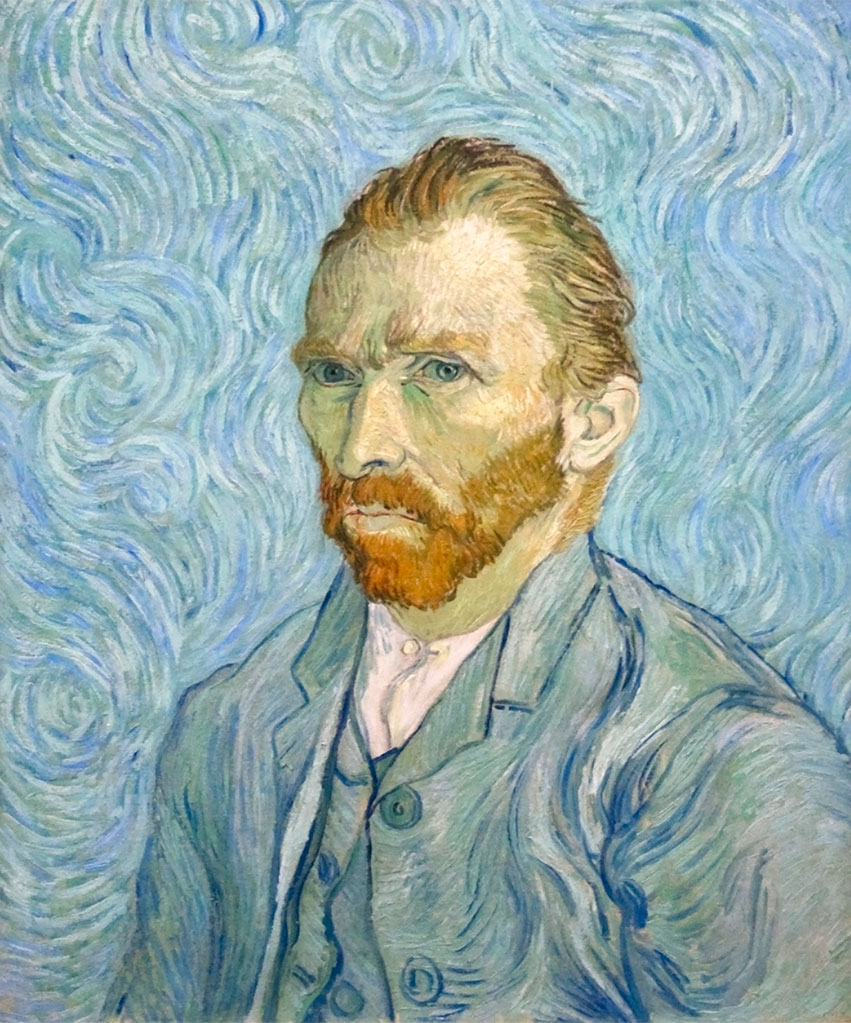

Lacking suitable models, he painted self-portraits or found inspiration in works of artists he admired. And when he was forbidden to work during a period after he tried to poison himself with his paints, he focused on his drawings. “The main thing is to keep on working,” he wrote in one of his letters.

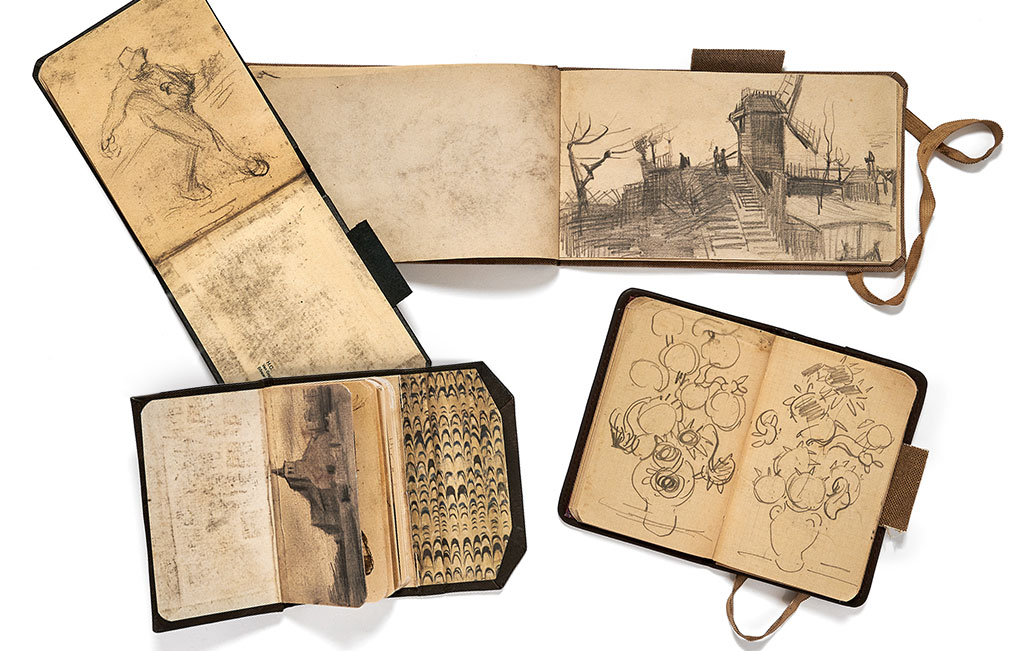

Still life of the four Van Gogh notebooks included in the work Vincent’s Gaze by ARTIKA.

Starting from scratch

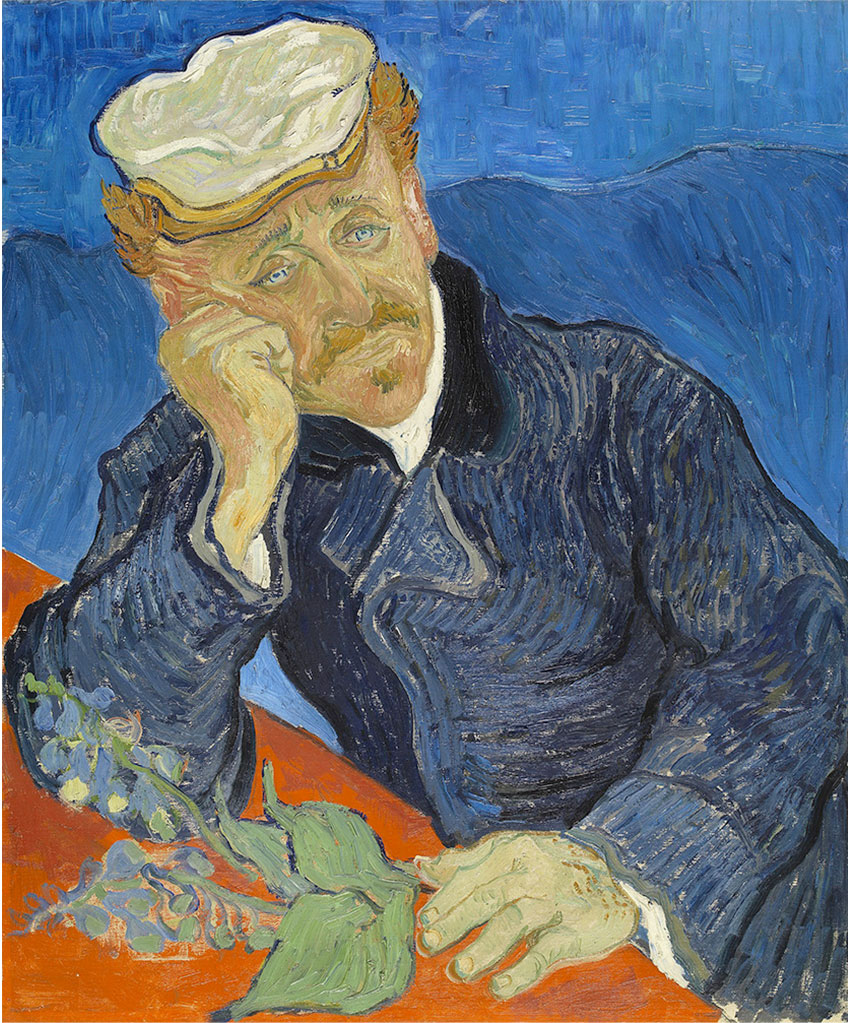

Van Gogh left the asylum on 16 May 1890 and settled in Auvers-sur-Oise under the supervision of Dr Paul Ferdinand Gachet, a friend of Théo’s. Vincent continued tirelessly to paint gardens, wheat fields, the church of Auvers and the famous portraits of Dr. Gachet. He experienced an intense recovery of his creative strength. Then, on 29 July 1890, Vincent shot himself in the stomach while painting in one of the fields that had been such an inspiration to him. He died after an agonising 36 hours.

Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890. Oil on canvas, 68 x 57 cm. Musée d’Orsay, París.

A decisive turn

Van Gogh might have been sent to a much more overcrowded asylum in Marseilles if had he not been admitted to the one in Saint-Rémy, where he would have been denied the freedom to move around and the luxury of continuing to paint. This would have increased the suffering of his final days and he would likely not have left us with some of his most admired work.

Self-portrait, 1889. Oil on canvas, 65 x 54,5 cm. Musée d’Orsay

A misunderstood talent

People often have a one-dimensional image of Van Gogh: the short-tempered genius with irrational outbursts. But when you read his letters, you discover someone who worked tirelessly, forever in search of a language all his own, like the one he developed through his expressive use of colour. As he himself noted, “Instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use colour more arbitrarily, in order to express myself, more forcefully.”

Not only did he anticipate Expressionism, but he also opened the doors to modernism. The talent that made Vincent van Gogh unique did not lie in his emotional instability. In other words, his genius as a painter was possible despite his mental illness, not because of it.

The artist and the human

Van Gogh’s letters provide a glimpse into his state of mind and his worries as an artist. They are accompanied by sketches and drawings where the artist used to show to his brother the evolution of his ideas. They are also highly valuable for their narrative quality. Hence, they are the most important set of private documents ever preserved by an artist.

This correspondence is brought together, along with the artist’s sketchbooks, in an exclusive ARTIKA publication: La mirada de Vincent (Vincent’s Gaze) a now out-of-print edition created in collaboration with the Van Gogh Museum.