Michelangelo through the sight of experts

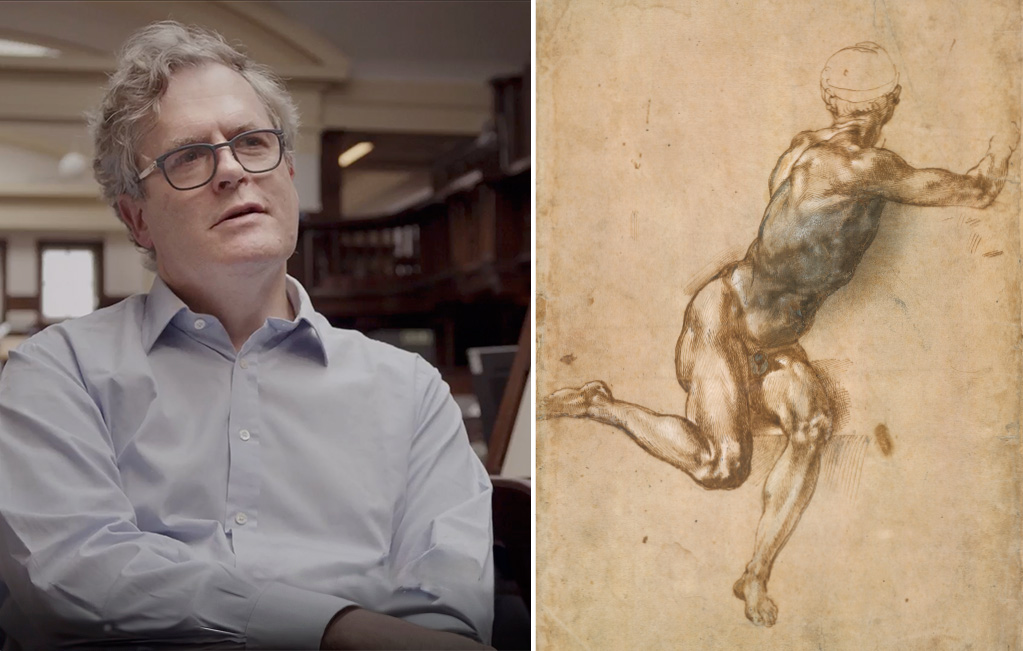

Hugo Chapman —Simon Sainsbury Keeper of the of Prints and Drawings Department at the British Museum— and Sarah Vowles —the Smirnov Family Curator of Italian and French Prints and Drawings at the British Museum— have spent years forming a relationship with the Florentine artist, studying him closely and living with him, in a way, within the museum walls.

On the occasion of the edition Michelangelo: Drawings, ARTIKA and the British Museum have joined forces to offer a broader profile of Michelangelo. The interviews, reflections, and essays by these experts, included in the Study Book, come as close as one can get to a one-on-one conversation with the Renaissance genius.

Creation: the idea in three dimensions

“The drawing is very layered. There’s one layer and then he’s drawing on top of that layer and then he’s drawing on top of that, so it’s incredibly dense and rich and you can spend a lifetime looking at it and seeing new things about it.” – Hugo Chapman

Left: Hugo Chapman, Simon Sainsbury Keeper of the of Prints and Drawings Department at the British Museum.

Right: Study of a seated nude man for the battle of Cascina, 1504–1505. Pen and brown ink, grey and brown wash heightened with partly discoloured white over leadpoint and stylus, 419 × 286 mm.

Whether drawings, frescoes, or sculptures, Michelangelo’s works are perceived as volumes. Each figure and element claim, without giving any evidence, to be flesh and bone, even when rendered in charcoal, chalk, or marble.

For Michelangelo, the idea was born already possessing the appearance it would have at the end of its creation. Consequently, he was forced to break down that robust fiction into layers, like a painting suddenly turned into a puzzle; he would ponder where to make cuts and how many pieces could preserve its integrity.

Always thinking in three dimensions, he drew on paper what he could not mentally envision in a flat form. This was the only way he could see volumes as something achievable: sketches, layer by layer, which he would attend to and then overlay until he reached the third dimension—for sculptures—or that sense of volume—in his paintings.

“He was very interested in the figure not as a flat, decorative form, but as something that is physically tangible. He as always thinking at the back of his mind about how something could be translated into marble. […] It’s always that sense of space which he comes back to.” – Sarah Vowles

Works: the plausible within the impossible

“It’s genius, being able to create figures that look completely convincing, even if sometimes we come to understand that the poses are anatomically impossible.” – Sarah Vowles

Left: Sarah Vowles, Smirnov Family Curator of Italian and French Prints and Drawings at the British Museum.

Right: Study of the lamentation, 1530–1535 Black chalk, 281 × 268 mm.

No one questions Michelangelo, for it’s so often called the master of human anatomy. A body robust yet gentle in movement, exuding both the elegance of wind and the firmness of skin and muscle.

When an expert evaluates him, there’s both the risk of killing the magic and the chance for admiration to grow even further. Beyond creating unattainable bodies, he subjected them to incredibly elaborate, even impossible, poses, which he resolved through harmony and ideal precision. This is how Michelangelo makes us confuse fascination with the certainty that we’re witnessing something real.

Grandiosity becomes absurd to the point that we feel we have a better grasp on what’s complex rather than what’s simple. The more detailed a story, the more truthful it appears—though all its nuances may be invented. We surrender to his utopia, too, captivated by the beauty of those men through the eyes of a narcissistic humanity, which does not rule out the possibility of seeing its own image in them.

“This cannot be a life model. It must be something Michelangelo has created. But […] we believe him and he captivates us into believing something which, although it’s incredibly beautiful, cannot possibly be true.” – Sarah Vowles

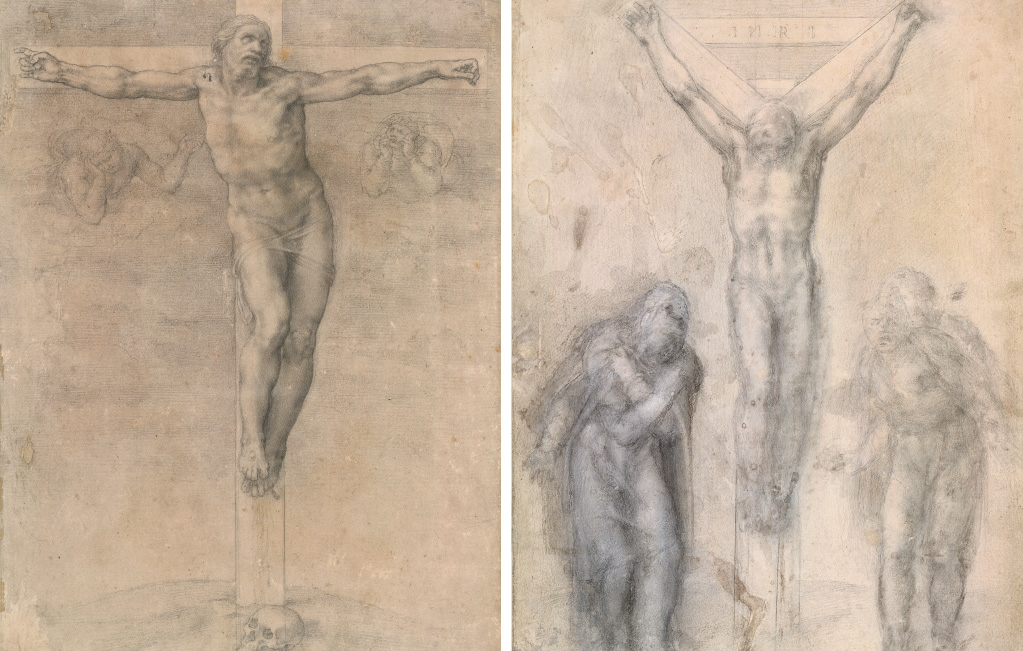

Art: youth in chalk, old age in charcoal

“At the end of his life, he’s drawing the dead Christ, this sort of ruined, broken body right at the end of his life. There’s these extremes of youth and old age, vitality and death.” – Hugo Chapman

Michelangelo’s stage of life can be sensed through the drawings that preceded his finished works, both by their themes and the materials used in each layer.

In his youth, his creations revolved around his own idea of vitality, expressed through a hyper-muscular body. The Michelangelo of the early 16th century was more independent and introduced a new technique: chalk, especially red chalk. Unlike charcoal, which is rigid, rough, and precise, chalk is malleable. He used it mostly for anatomical studies, as the color and texture evoked and simulated flesh.

Left: The fall of Phaeton, 1531–1533. Black chalk, over some stylus underdrawing, 312 × 215 mm.

Right: Figure study for the Last Judgement, 1534. Black chalk, 404 × 270 mm.

From around 1530 onward, he turned more toward charcoal and ink, with which he could blur at will and with less precision. With this technical shift came a paradigm change: he was no longer interested in the solidity of the body because he, as a person—not just as an artist—was losing it.

“Those last, final drawings, the drawings of the crucifixion, are really a form of prayer, a way of meditating on that coming death. And so, they’re incredibly moving to me because they’re about and old man coming to terms with the end of his fears and his hopes.” – Hugo Chapman

Left: Study of Christ on the cross flanked by two angels, 1538-1541. Black chalk, 368 × 268 mm.

Right: Study for Christ on the cross between the Virgin and St. John, c. 1555-1564. Black chalk highlighted with discoloured white lead, 412 × 285 mm.

Life: a very private and possessive man

“When he’s in Rome, he’s writing back to his father. He’s saying: ‘Don’t allow anybody to look at my drawings’. […] There are artists who were quite free and easy in allowing people to look at their drawings, but Michelangelo really, really did not like it.” – Hugo Chapman

The British curators reveal peculiar insights that help us understand the artist as a man. While the greatest fear of most men is dying alone, Michelangelo’s fear was living in company. He avoided sharing time and space with other artists, not just because he liked being by himself, but too because he was extremely distrustful: he feared they would steal his art—his only tolerable and well welcomed companion.

“It’s, sometimes, quite a dark place to spend your life with Michelangelo, because he spent a lot of his life complaining about others. But there’re sort of moments when he’s funny and becomes terribly alive.”– Hugo Chapman

Michelangelo: an undisputed favorite of the British Museum

“I would be lying if I didn’t mention the study for Adam on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, which for me is just one of the most spectacular drawings ever made. It is a tremendous exploration of the human form in its most beautiful and most perfect interpretation and it is something which, even now, has the power to amaze people. It really is an icon of the historical approach to the world.” – Sarah Vowles

Study of Adam for the Sistine Chapel, c. 1511. Red chalk over some stylus underdrawing, 193 × 259 mm. Purchased with contribution from Art Fund (as NACF), Joseph Duveen, Baron Duveen of Millbank and Henry Van den Bergh.

All knowledge seems in vain when it comes to determining a favorite work by Michelangelo; each stands out for everything and nothing at once. Still, one answer may be predictable—but never wrong: to deny the mystery and fascination of the Sistine Chapel would be an offense not only to the painter but to art history itself.

“What’s the most important drawing in the British Museum? It’s a bit like asking somebody with many children which is the most brilliant of them or the one that they prefer. I mean, I would certainly say the red chalk Adam, because it’s related to the creation of man, […] because it’s become an icon of Western art.”– Hugo Chapman

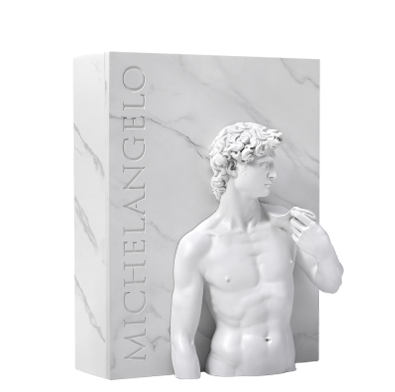

‘MICHELANGELO: DRAWINGS’ – An artist’s book unpacking the Renaissance genius

-A numbered and limited edition of 8,998 copies.

-The edition consists of two volumes, gathered in a sculpture-case that incorporates a reproduction of David in its design.

-The Art Book, hand-bound, includes 75 drawings, 35 of which are reproduced in their original size. It features works spanning his entire life, from age 20 to just before his death at 88.

-All plates are printed with the museum’s copyright and individual numbering on the back.

-In the Study Book, British Museum experts analyze each of the works included in this edition.

-In addition, the texts reveal the key traits that define Michelangelo’s drawing style, through his story and technical innovations.