Extracts from Sorolla’s vital and graphic diary

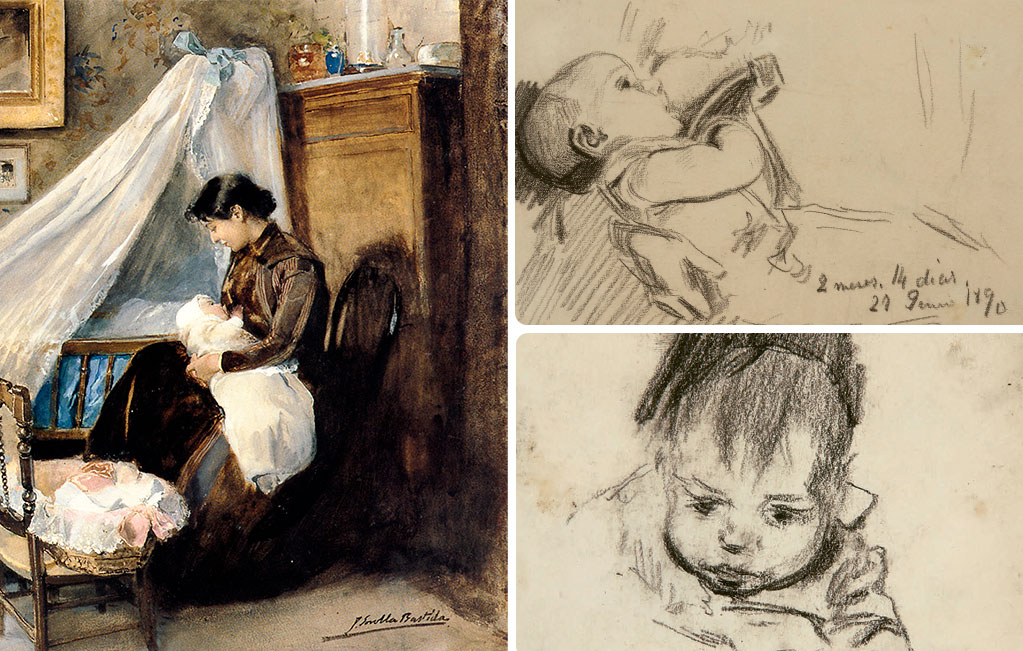

MARÍA AT TWO MONTHS, 27 June 1890

María is the couple’s first daughter, marking a second turning point in Sorolla’s artistic career after Clotilde. Her birth makes him a father for the first time, consolidating his private side, where family shares space with his art.

Drawing Clotilde breastfeeding María, or rather, María clinging onto Clotilde’s breast, is intimate not only due to the mother’s nudity but also because of the purity of a life that, even though the umbilical cord has been cut, still belongs to both of them.

María, just over two months old, is not capable of registering or storing information; she will not remember her first days on earth. She might look at her mother with wide-open eyes, but these images she does not record. This is when Sorolla, being more of a father than a painter, captures his version of the scene. He does not steal that memory from María; instead, he preserves it for her to see when she grows up—something that, for a parent, happens in the blink of an eye but can be saved in charcoal on paper. In this case, it comes to life with light and color, in a much broader composition, in the painting The First Child (1890).

Left detail of the painting: The First Child, 1890.

Right, superior: María at two months, 27 June 1890.

Right, inferior: María, 1890.

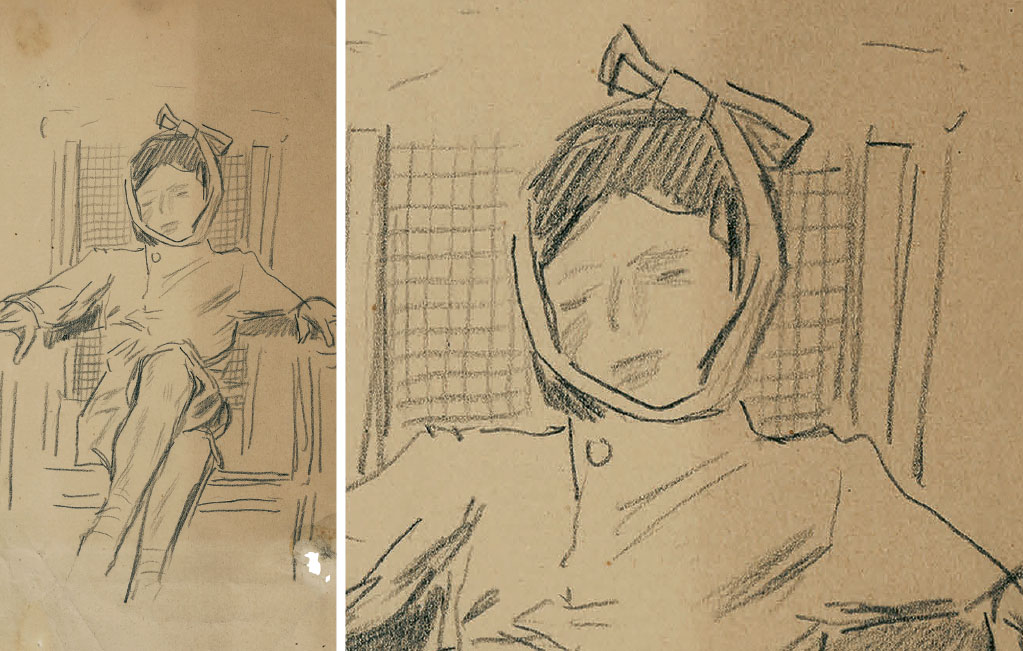

CLOTILDE WITH HELENA, 1895

The drawings of Clotilde with her three children in their early years share similarities in composition and technique. Often, we see her in profile, holding them or simply being by their side. In this piece, neither of their faces are visible, reinforcing the idea that Sorolla is not pursuing a portrait—just a face and its background—but rather the moment itself, in its entirety.

There is a clear parallelism in their bodies, with the hair of both mother and daughter replacing facial expressions. Clotilde unconsciously mirrors Helena’s body posture, as if by instinct. Nothing is more intimate than the unconscious imitation of another’s gestures. Bodies act as mirrors of those in front of them, an undeniable sign of complicity that goes beyond routine. These are maternal tendencies that become reciprocal, filial.

Unlike some paintings, which—under the pressure of being exhibited—cannot escape a certain level of artificiality or planning, this composition is subjective and spontaneous. One can imagine bold colors in the charcoal-filled areas, lighter tones, or the position of the light in the empty spaces and shapes. However, when a drawing is not meant to become a painting, light and dark are not necessarily about color but about emphasizing certain elements over others: Clotilde and Helena as a single entity, their connection as the luminous source of the room.

Clotilde with Helena, 1895.

JOAQUÍN WITH TOOTHACHE, c. 1900-1901

Drawing was a constant for Sorolla, yet not a homogeneous practice. At times, he lived for the details; at others, he preferred a more schematic style. Here, Joaquín’s body seems indifferent to his toothache—sitting upright, even crossing his legs. It is in his face, with just four straight lines, that emotion pours out. The dissonance between how his body and face respond to the situation perfectly conveys this first step toward a more mature stage of life, gradually leaving childhood behind.

Beyond his posture and facial expression, the tooth itself is also symbolic. Teeth do not grow with us; they fall out to be replaced. Arms, legs, and the torso do not change—they grow longer, wider; the elasticity of the skin allows for expansion without replacement. But milk teeth literally fall out, shedding when it’s time to grow up —childhood we lose through tangibility.

Little Joaquín finds himself in a moment of vulnerability, but so does the painter, who looks into his son’s growing pains, in every sense of the term. His upright posture signals self-control and independence, while his contracted face reveals a need for comfort, perhaps something only his father can provide.

Joaquín with toothache, c. 1900-1901.

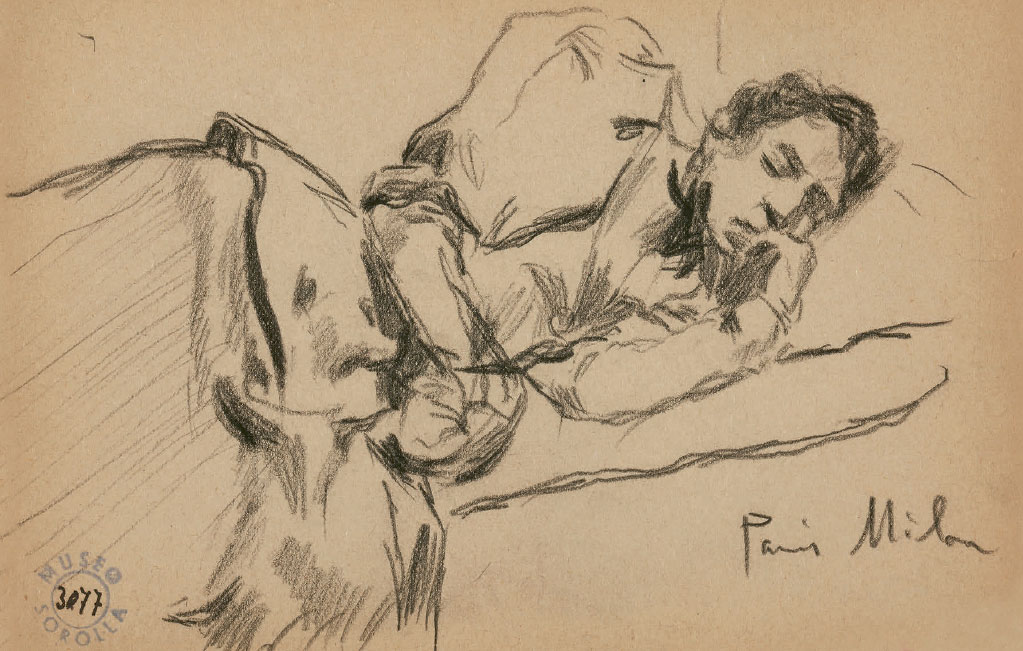

CLOTILDE SLEEPING, June 1897

Sorolla captures that intimate act of watching someone who is unaware of being looked at, but on a deeper level. To admire a body and a mind at rest, someone asleep and, therefore, completely unguarded.

Much of Sorolla’s graphic work reflects an observant, restless, and tireless personality, passionate about his art and finding new means of expression. While some of his drawings are preparatory studies, others are genuine and instant impulses that don’t exist in the future tense, and so what they need to be, they are, solely in a present form. This is a private moment, one he is conscious of while his wife is not. Sorolla paints Clotilde in a moment she does not share with him, and his way of being part of her world is to respect that temporary retreat into the subconscious, to sit before her and draw.

Many of Sorolla’s family drawings are not posed, but rather everyday scenes he captures precisely when his subjects are too absorbed in their own lives to notice him. Sleep is perhaps the ultimate example of this—of being completely unaware of being observed—allowing this composition to reflect the sincerest naturalness.

Clotilde sleeping, June 1897.

CLOTILDE WITH HER CHILD, c. 1891-1892

The identity of the baby in this drawing was revealed for the first time in the Clotilde de Sorolla exhibition. Upon restudying sketches and verifying inscriptions for Sorolla in Private, it was determined that the child in the drawing is not Joaquín (as stated by Inés Abril Benavides and Mónica Rodríguez Subirana in their article ‘Commentary on Selected Family Drawings’ included in the Study Book).

Clotilde is lying on the floor, reaching out to María, while the little girl pulls her hands back—not to distance herself, but to clap. The scene is viewed from an interesting perspective, both the positioning of the bodies and the intimate, domestic setting. Lying on the floor is an ordinary and private act; one does not think to do it outside, one does not rest their back, ruffle their hair, or wrinkle their clothes in public or in someone else’s house.

Moreover, Sorolla may be drawn to this moment because of how his family organizes itself. Clotilde lowers herself to the floor to create a spatial balance with her daughter, making it easier to meet her gaze—a silent, confidential, private dialogue.

Clotilde with her child, c. 1891-1892.

Truer than truth itself

“These are the hours I shall devote to you. I can find no better time to communicate with the woman I love best; I have your portrait before me, and believe me, I did well to bring it, for despite painted by my own hand, there is something in it truer than truth itself; I have had it mounted on a dark green card, and it looks very fine.”

Letter 55 [From Sorolla (Valencia) to Clotilde (Madrid).

23 and 24 November 1907. CFS/430 bis]

In order to truly know Sorolla, paintings and drawings are not enough. His letters to his wife reveal another facet of who he was as a person and, consequently, as an artist. The distance between his home in Madrid and his various destinations was bridged by letters, which now form the Correspondence: Three Decades of Love in Sorolla in Private.

This passage confirms the value that drawings held for him. He did not carry a painting or a photograph but rather a sheet of paper, a sketch of fluid and spontaneous strokes that preserved the sentiment and emotion of the moment—something that would have been lost in the time-consuming precision required for a canvas painting. This is why he carried them along his travels and the reason he liked to describe them as “truer than truth itself.”

SOROLLA IN PRIVATE: family as the muse of his most personal art

-A limited, numbered edition of 2,998 copies, produced in collaboration with the Sorolla Museum and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the painter’s great-granddaughter and trustee of the foundation.

-It includes two volumes, a correspondence, and an art print, all enclosed in a display case featuring a detail from the oil painting Instantánea, Biarritz (Snapshot, Biarritz), which serves as the cover for the Art Book.

-The Art Book includes 71 of Sorolla’s most personal drawings, previously preserved in his sketchbooks. The selection, assisted by the Sorolla Museum and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, has been die-cut and reproduced at full scale with the highest quality.

-The Study Book features analyses by Inés Abril and Mónica Rodríguez on each drawing, while essays by Consuelo Luca de Tena, María López, Covadonga Pitarch, and Eulalio and Pilar Pozo explore the themes of family and the conservation of Sorolla’s graphic work.

-Correspondence: Three Decades of Love contains 210 out of the 2,000 surviving letters. Introduced by Isabel Justo, the correspondence serves as both a socio-economic and political testimony of its time and a passionate love story.

-The edition includes the print Estudio al natural, 1905, a charcoal, chalk, and red oil portrait of Clotilde that adorned their bedroom for years.