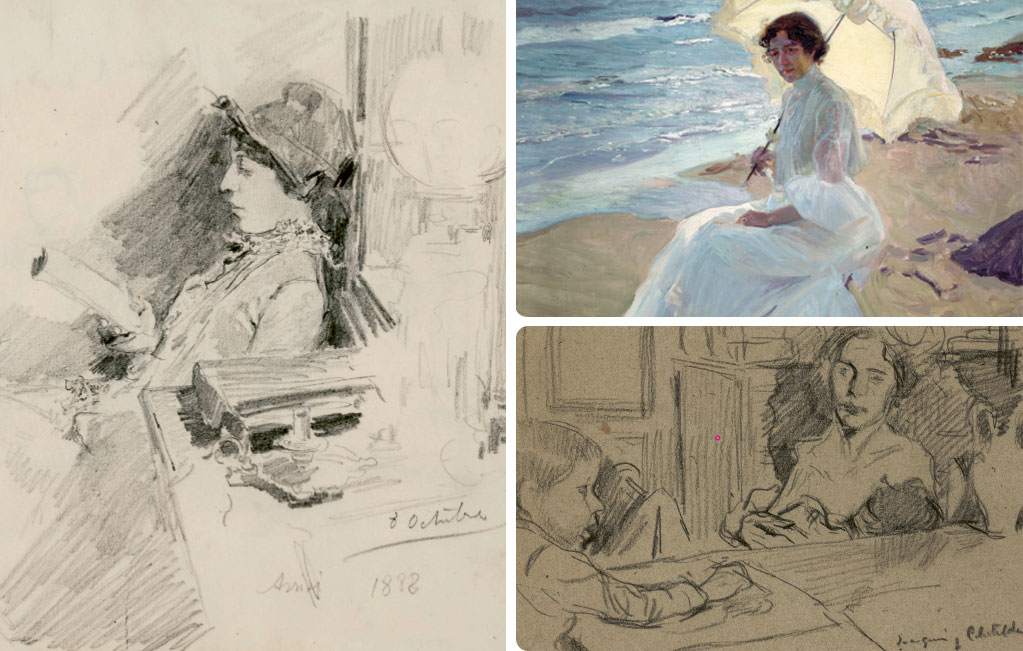

Clotilde: a timeless and ever-present woman

Clotilde García del Castillo, exhibition curator and wife of the luminist genius Joaquín Sorolla, is revealed through art as a woman both of her time and unexpectedly ahead of it during an era of “separate spheres”: the public sphere belonged to men and, the private sphere, to women. Through Sorolla’s paintings, drawings and letters, she emerges as a woman of many roles, both in the family and in society. These are the themes explored by curator and researcher María López Fernández in her article “Sorolla. The Image of Clotilde”, included in the Study Book of the edition Sorolla in Private.

Clotilde’s temporal duality

“Woman was born for no purpose other than to be woman: that is, to be man’s helpmeet, […] his mother, his wife, his daughter […], his angel of charity in his tribulations and his beacon of hope in moments of despair,” according to books on morality.”

Sorolla paints Clotilde timeless and omnipresent: out of her era, yet a representative of it. Paintings, drawings, and sketches portray her reading, walking along the shore or strolling through gardens, simply existing, both as a free individual and as a devoted wife and mother. Whether captured on canvas or paper, Sorolla’s work is full of admiration for Clotilde in her maternal, marital, and personal roles. She is not boxed in by the artistic conventions of her time; she is often portrayed as a good mother or excellent wife, but those are far from her only—or defining—qualities.

“[he radically altered] the humiliating paternalistic attitude towards women that had characterized the school’s past. The essential feminine archetype was still that of woman as mother and wife, but she was no longer considered fragile as a child or kept locked up like a nun: the new woman was strong and fertile, the source of all order, clarity and harmony.”

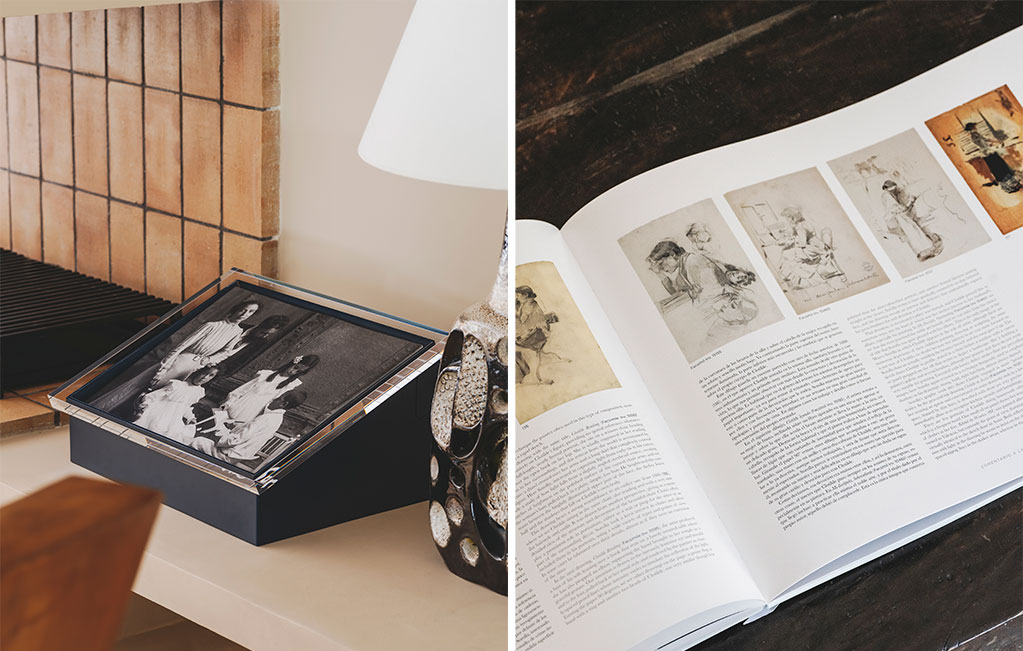

Left, drawing detail: Clotilde leyendo (Clotilde Reading), conté crayon on roll paper. Asís, c. 1888.

Right Sup., detail of the painting: Clotilde en la playa (Clotilde at the Beach), 1904.

Right Inf.: Joaquín y Clotilde (Joaquín and Clotilde), 1898.

Mother: the painting that introduced motherhood in Sorolla’s work

This painting marks two stages in Sorolla’s artistic journey, spanning before and after the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition. Initially, Mother (1895–1900) showed Clotilde with their daughters María and Elena, her gaze turned toward the artist. In 1900, Sorolla made a subtle but significant change: Clotilde’s gaze shifts away from him to rest on little Elena.

In the first version, Clotilde’s look toward Sorolla positions her more as a wife than a mother, as it makes him the implied off-canvas protagonist. After the change, the work launches one of the central themes of Sorolla’s oeuvre: motherhood.

Madre (Mother), 1895-1900.

Clotilde’s wardrobe in the dialogue between society and art

Clotilde’s image is like a family diary. Through her expressions, postures, outfits, and colors, we get a glimpse into the family’s social and economic standing.

“In The Custom of the Country, Edith Wharton wrote that the principal requirement of a portrait was “that the costume should be sufficiently lifelike, and the face not too much so”.

So much so that painting began to influence fashion itself. Between artistic and activist circles, associations of women artists emerged calling for simpler dresses, a way of reclaiming agency within their own portraits. These were not mere suggestions but clear, goal-oriented movements seeking fair and balanced representation. Hence the creation of groups like Circle of Women Painters (Brussels, 1888), following the lead of France’s Union of Women Painters and Sculptors (1881). Yet ultimately, the outfit whispered to the artist what the painting demanded: to visually communicate social and class politics, so it could not be detached from the woman who wore it.

“For the nobility and upwardly mobile haute bourgeoisie, portraiture was a social statement, a way of displaying their power and lofty status in a world where appearances were everything.”

Left: Clotilde con traje gris (Clotilde in a Grey Dress), 1900.

Middle, detail of the painting: Clotilde con traje negro (Señora de Sorolla in Black), 1906.

Right, detail of the painting: Clotilde en el jardín (Clotilde in the Garden), 1919-1920.

Take Señora de Sorolla in Black (1906), whose preparatory sketch is featured in Sorolla in Private as the edition’s art print. The dress, with its patterns and structure, wraps Clotilde in elegance and eccentricity, balanced by the sobriety of black.

This was a time when Sorolla exposed tensions between the suffragist movement—fighting for women’s emancipation—and the era’s prevailing notions of femininity imposed through clothing that didn’t exactly encourage free movement. Still, we don’t see Clotilde in tight corsets, but in garments that appear soft and flowing, much better suited to seaside strolls.

Maternal instinct toward life itself

Through their letters, Sorolla and Clotilde offer more than glimpses of love or family anecdotes. Each letter forms a parallel account of their everyday lives, offering a private, intimate lens on the social, economic, political, and artistic landscape of the time. Whether directly or between the lines, the letters portray Clotilde as both wife and mother, but in ways that go beyond the standard social definition, always preserving her individuality.

“What did you decide today which you believe will be advantageous to our prospects? Is it a contract of some kind for a decoration on a portrait series? As you explain nothing and give me no details, you leave me in suspense and pondering what it might be.” Letter 64 – [From Clotilde (Madrid) to Sorolla (London). 18 May, 1908. CFS/616]

To Sorolla, Clotilde’s motherhood encompassed every aspect of her personality—not only when it involved him or their children. He saw her maternal spirit in her instinctive bond with the things she loved: love and family, yes, but also art and the sea.

“The sea today has a sublime blue intensity, and the dates shimmer like gold nuggets. All this makes me regret that for the sake of little things you are not enjoying it with me.” Letter 196 – [From Sorolla (Alicante) to Clotilde (Madrid). 25 December, 1918. CFS/1935]

Left Sup.: Clotilde con Joaquín y María (Clotilde with Joaquín and María), conté crayon on cream paper, 1896.

Left Inf.: Mi mujer y mis hijas en el jardín (My Wife and Daughters in the Garden), 1910.

Right Sup.: Bajo el toldo, playa de Zarauz (Under the Awning, on the Beach at Zarauz), 1910.

Right Inf.: Clotilde con su hijo (Clotilde with her child), charcoal on roll paper, c. 1891-1892.

Sorolla in Private, a declaration of love to his wife and children

– A numbered and limited edition of 2,998 copies, created in collaboration with the Sorolla Museum and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the artist’s great-granddaughter and trustee of the Foundation.

– It consists of two volumes, a letter collection, and an art print, all presented in a display case featuring a detail from the oil painting Snapshot, Biarritz, which also appears on the cover of the Art Book.

– The Art Book includes 71 of Sorolla’s most personal drawings. Selected with assistance from the Sorolla Museum and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, they have been die-cut and reproduced full-scale with the highest quality.

– In the Study Book, experts Inés Abril and Mónica Rodríguez analyze each drawing in the collection, while Blanca Pons-Sorolla, Consuelo Luca de Tena, María López, Covadonga Pitarch, and Eulalio and Pilar Pozo explore themes of family, as well as the conservation and restoration of the artist’s graphic work.

– The Correspondence: Three decades of love features 210 letters from the 2,000 preserved. With a foreword by Isabel Justo, these correspondences offer a socio-economic and political snapshot of the era, while also reading as a passionate and familial love story.

– The edition includes the print Study from Life, c. 1905—a portrait of Clotilde in charcoal, white chalk, and red oil—that hung above the couple’s bed for years.