A portrait of childhood: María, Joaquín, and Elena on canvas and paper

As an artist, Sorolla didn’t consider himself a portrait painter beyond the commissions he received from the Spanish and American high society. In the drawings of his family, that formal quality of portraiture dissolves into the intimacy of the setting; the posed aspect is lost because the painter wasn’t searching for the moment —it found him instead, like a wonderful, unexpected gift captured with a spontaneous, bold and sincere stroke. His artistic self could not be separated from his role as a father.

Scenes featuring his children were often shared with the public in exhibitions like the National Exhibition of Fine Arts (1887) or the 1906 show at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. However, Sorolla primarily drew them for himself, to freeze time and hold on to the fleeting essence of childhood, which felt even more ephemeral to him as a father. So, although the faces of María, Joaquín and Elena were exhibited in Germany (1907), London (1908), and even the United States (1909 and 1911), they were most cherished at home, in the family household.

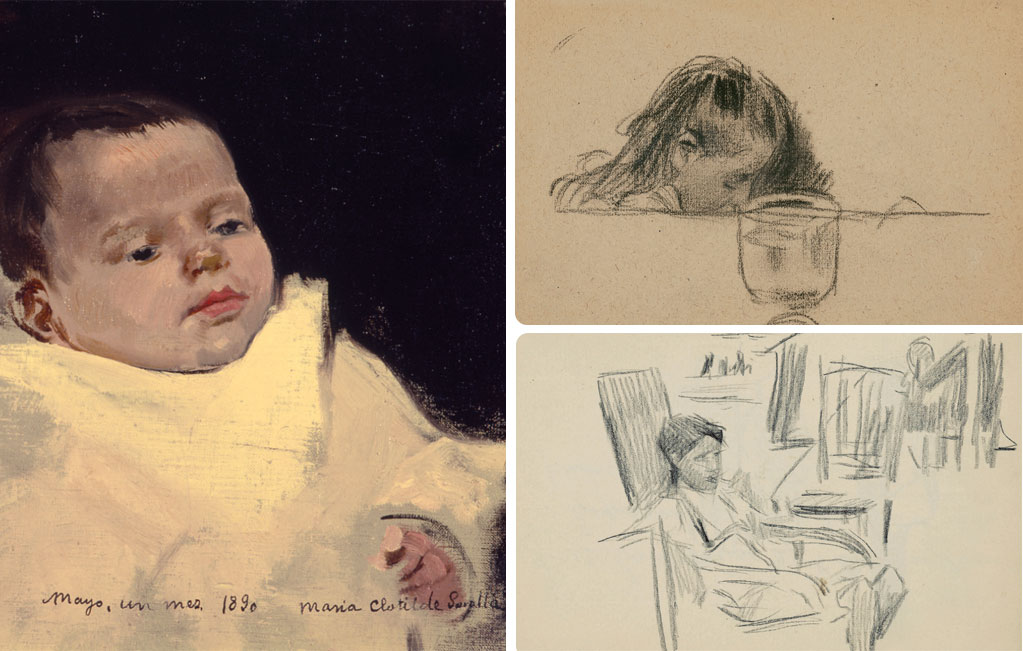

María, the heir to artistic talent

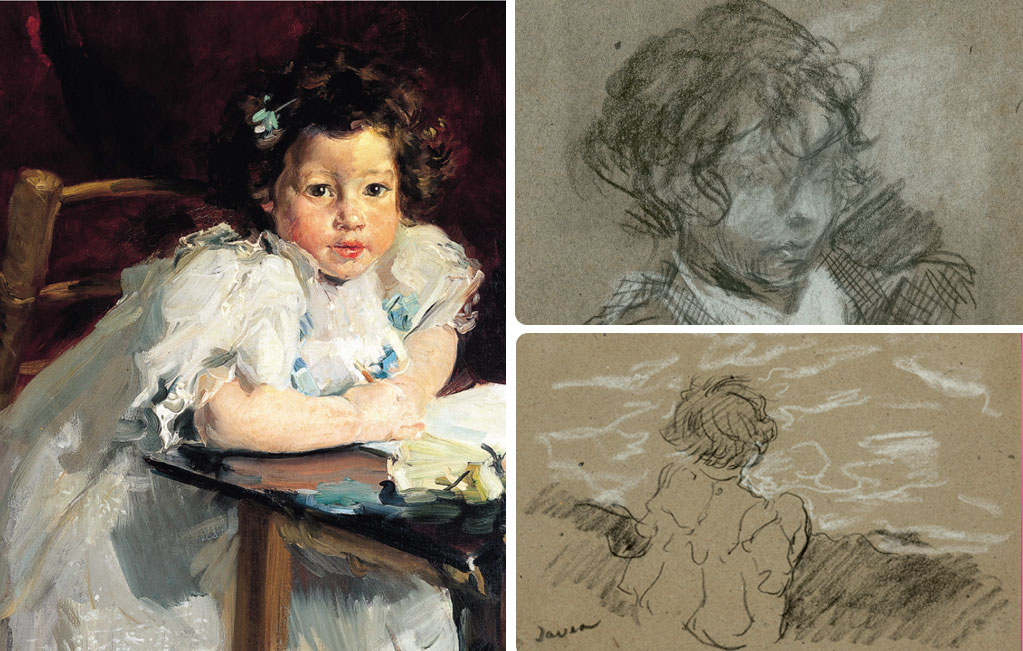

The first portrait of his children is of newborn María—María Clotilde Sorolla García (1890)—in which the simple color palette and the unfinished effect in the lower half of the canvas draw the viewer’s focus to the baby’s face. The painter’s joy is more apparent when painting family members, as already seen in his portraits of Clotilde. The brushstrokes are looser, broader—signs of the ease and affection with which he painted them.

Sorolla’s habit of always carrying paper and charcoal means that drawing, more than painting, is what consistently captures his children’s growth —an ever-alert gaze seeking out the moment. Tireless and constant, his sketches admire María when she believes no one is watching: resting after lunch, as in Child’s Head (1897–1898), or swaying in María in the Deckchair (1900). These works show how he portrayed his daughter’s childhood without ever needing her to pose.

Left: Detail of the painting María Clotilde Sorolla García, 1890. © Museo Sorolla, Fundación Museo Sorolla, 2014.

Right Sup.: Child’s Head, c. 1897-1898.

Right Inf.: María in the Deckchair, c. 1900.

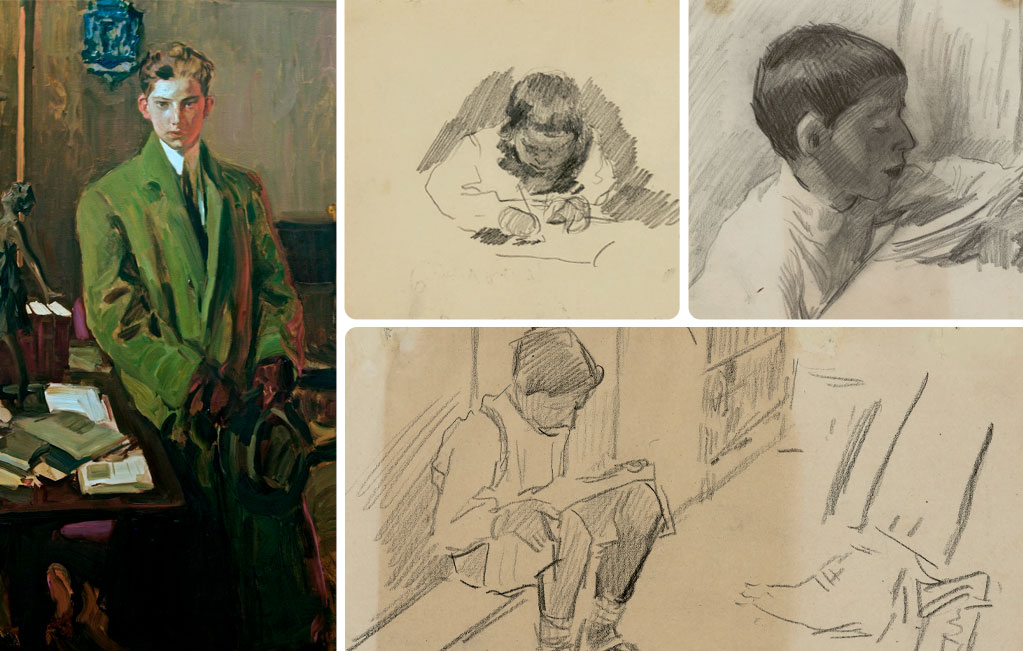

Joaquín, the model student

As the only son in the family, Sorolla and Joaquín shared a special bond. Unlike María, who eventually pursued painting as an adult, Joaquín didn’t show interest in color and its blends, but rather in their chemical compositions, which led him to study engineering—a degree he was unable to complete due to the outbreak of World War I.

Moments from his childhood captured in pencil do reveal that Sorolla’s artistic streak touched all his children, to varying degrees, as seen in the drawing Boy Drawing (1896). Yet ultimately, Sorolla’s admiration for Joaquín is expressed through his identity as a model student, a recurring theme in portraits that often show him surrounded by books—such as the sketch Joaquín Reading and Legs (1900–1905)—or illuminated by the soft glow of his desk lamp, where he spent countless hours studying, as portrayed in To My Son Joaquín (1911).

Left: Joaquín, 1911. © Museo Sorolla, Fundación Museo Sorolla, 2014.

Medium Sup.: Boy Drawing, 1896.

Right Sup.: Joaquín Sorolla García, c. 1900-1905.

Right Inf.: Joaquín Reading and Legs, c. 1900-1905.

Elena, the soul of the house

Alongside her mother, Elena appears in one of Sorolla’s most iconic works: Mother (1895). This painting depicts Clotilde, exhausted after giving birth to their youngest child. Both the monochromatic tones and the brushwork reflect Sorolla’s deep respect and admiration for them: not only it’s a portrait of the figures, but of the love and intimacy that radiates from their bond.

Individually, his paintings often portray Elena playing, whether with dolls, dressing up as a lady-in-waiting or doing her homework, just like it is underlined in Elenita at Her Desk (1898). His private sketches emphasize her face, curly tousled hair —as seen in Elena in Jávea (1900–1901)—and her expressive personality: always cheerful or curious, for instance, in Elena (1900–1901). These traits go beyond mere physical appearance, revealing the child’s essence: strong-willed, energetic, and joyful.

Left: Detail of the painting Elena at her desk, 1898. © Museo Sorolla, Fundación Museo Sorolla, 2014.

Right Sup.: Elena, c. 1900-1901.

Right Inf.: Elena in Jávea, 1900-1901.

From María, Joaquín and Elena to Sorolla

Sorolla painted his children throughout their lives, not because time could be stopped, but because it was a way to live and express love. These images of childhood, so brief by nature, are immortalized by a father who, coincidentally, was also a painter. Eventually, this act of capturing them ceased to be a one-sided practice: the children, in turn, contributed to the legacy of their lives by leaving memories of their own. In their case, it took the form of letters sent to their father while he was away for work.

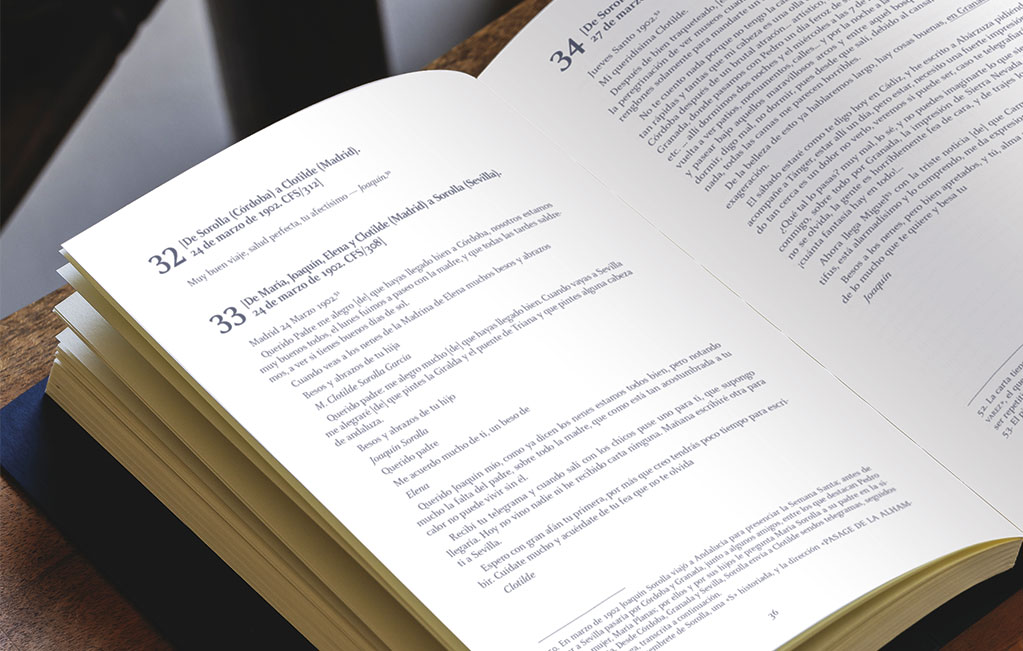

Some of these letters are published in Correspondence: Three Decades of Love, included in the Sorolla in Private edition. One such letter, dated March 24, 1902 (Letter 33 in the collection), features a change in authorship: Clotilde hands the pen to the children, and together they write to their father in Seville —one of many destinations in Sorolla’s travels.

At twelve years old, María writes as the voice of the oldest sister, updating her father on household news as much as expressing concern for his well-being:

“Dear Father, I’m glad you arrived safely in Córdoba, we are all very well, Monday we went out for a stroll with mother, and we shall go out every afternoon, hopefully you will have good sunny days.

When you see Elena’s godmother’s children give them heaps of hugs and kisses.

Hugs and kisses from your daughter

M. Clotilde Sorolla García.”

Joaquín, then ten, expresses interest in his father’s artistic work, beyond simply saying he misses him or wants him to come home:

“Dear father: I am very glad you arrived safely. When you go to Seville it would please me if you paint the Giralda the Triana Bridge and paint a few heads of Andalusian women.

Hugs and kisses from your son

Joaquín Sorolla.”

And Elena, given the fact she’s the youngest of them all and writes her part at age seven, showcases a more emotionally direct message, centered on how much she misses her father during his frequent travels:

“Dear father

I think of you often, a kiss from

Elena.”

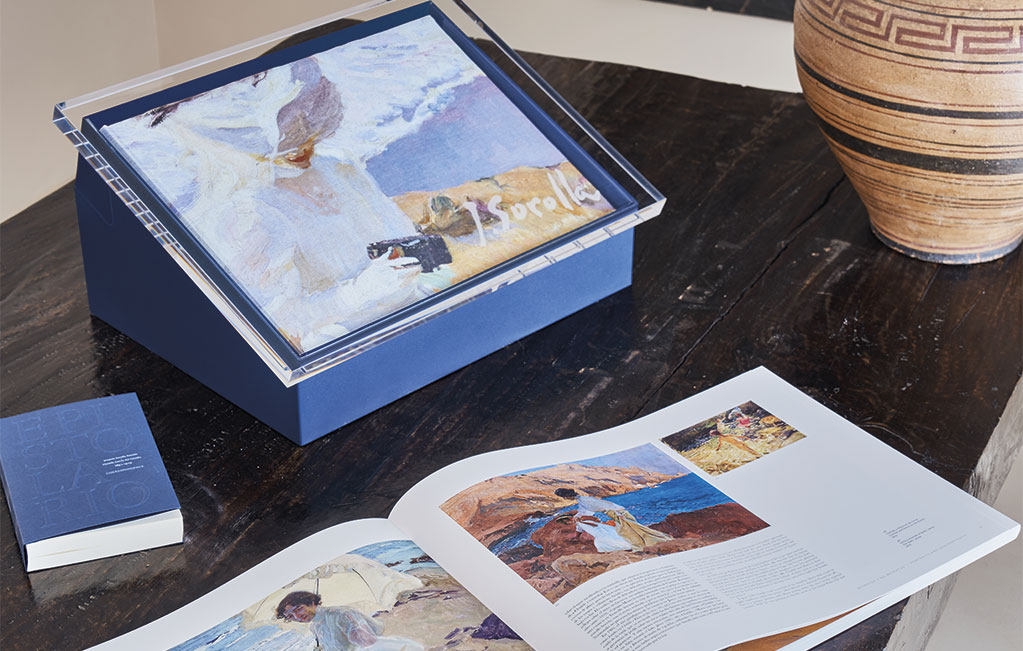

Sorolla in Private: art as a chest of memories

– A numbered and limited edition of 2,998 copies, created in collaboration with the Sorolla Museum and Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the artist’s great-granddaughter and trustee of the Foundation.

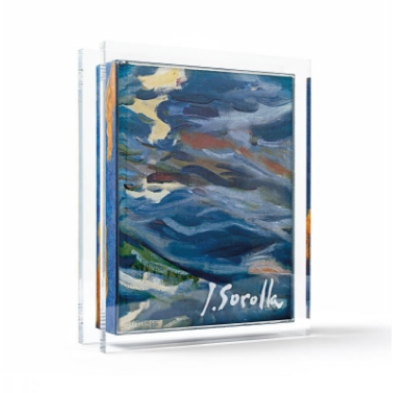

– It includes two volumes, a letter collection, and an art print housed in a display case featuring the painting Snapshot, Biarritz, the cover image of the Art Book.

– The Art Book includes 71 drawings that bring Sorolla’s most personal experiences into the family and domestic setting.

– In the Study Book, experts Inés Abril and Mónica Rodríguez analyze the featured drawings, while Blanca Pons-Sorolla, Consuelo Luca de Tena, María López, Covadonga Pitarch, and Eulalio and Pilar Pozo explore themes such as family and the preservation of the artist’s graphic work.

– Correspondence: Three Decades of Love compiles 210 of the over 2,000 known letters. Introduced by Isabel Justo, the correspondences offer a socio-economic and political testimony of their time, also read like a story of passionate and parental love.

– The edition includes the print Study from Life, c. 1905, a portrait of Clotilde in charcoal, white chalk, and red oil that hung in the couple’s bedroom for years.